By 1999, Abdullah Ocalan had become the world’s most prominent Kurdish figure and a fugitive driven out of several countries. Born in 1948 in southeastern Turkey, Ocalan became politically active during his college years and founded the PKK in 1974.

Ocalan’s vision, rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, was to set up an independent Kurdish state by waging an armed struggle against Turkey. The first shots of this conflict were fired in 1984, but it continues even now, having claimed, by some estimates, over 50,000 lives.

Since the PKK’s formation, Turkey has formally declared the group a terrorist organization, a stance adopted by the United States, the European Union, and much of the international community. Ocalan became an international fugitive since about 1980, when he fled to Syrian-controlled areas of Lebanon, where he set up his PKK headquarters. He was driven from Syria under international pressure and has sought safe haven in Italy, Russia, and Greece, where he arrived with two female aides on 29 January 1999. The group had been spirited out of St. Petersburg, Russia, on a private plane hired by a retired Greek Navy officer, a long-time friend of Ocalan’s.

PKK’s primary targets are ISIS, Arab jihadi groups (recent), Turkish Government security forces in Turkey and in Syria. PKK has also been active in Western Europe against Turkish targets. It conducted attacks on Turkish diplomatic and commercial facilities in dozens of West European cities in 1993 and again in spring 1995. In an attempt to damage Turkey’s tourist industry, the PKK has bombed tourist sites and hotels and kidnapped foreign tourists.

Strength

Approximately 10,000 to 15,000 guerrillas. Has thousands of sympathizers in Turkey and Europe.

Location/Area of Operation

Operates in Turkey, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

THE INTELLIGENCE OPERATION TO CAPTURE OCALAN

The six travellers arriving at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport looked like any other tourists on safari. They were casually dressed and carried huge jungle green backpacks. Nothing betrayed the fact that this party of five men and a woman were Mossad agents whose mission in the country would thrust Kenya into the international spotlight, expose its close ties to Israeli security services and cause a diplomatic row that saw then Foreign Affairs minister Bonaya Godana order all Kenyan embassies closed for a day.

The Israelis came to town because of the presence in Nairobi of Abdullah “Apo” Ocalan, at the time one of the world’s most wanted men. Ocalan was a terrorist to some and a liberator in the eyes of others. He led the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which was engaged in a long struggle to secure an independent state for the Kurdish people — an oppressed minority spread across a number of countries including Turkey, Iraq and Syria. Ocalan’s group was particularly active in Turkey, the country of his birth.

Turkey blamed him for the murder of between 29,000 and 37,000 people in a 15-year campaign of violence. “Wherever he goes in the world, we will pursue him,” then Turkish President Suleyman Demirel had vowed. “Those who befriend him are the partners of a baby killer.”

The circumstances under which he gained entry into Kenya remain a mystery, but suspicion falls on corrupt immigration officials. He was cleared for entry at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport despite being a wanted man in many countries around the world. The fact he carried a rifle with him and was accompanied by armed bodyguards did not prove an obstacle to the Greek embassy officials who facilitated his entry into the country.

Greece has long had difficult relations with Turkey and has been accused of supporting the PKK. They were reluctant to give the fugitive asylum in Greece but settled on Kenya as a hiding place where they would keep the Kurdish leader while trying to help him get asylum elsewhere.

Ocalan timed his arrival in Nairobi in January 1999 poorly. The US Embassy had been bombed only a few months earlier and, according to a New York Times report, there were more than 100 US investigators in the country. The Americans were the first to realise Ocalan was in town. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operatives tracked Ocalan to the Greek ambassador’s residence in Nairobi’s upmarket Muthaiga estate.

The Americans did nothing. But there was also another team tracking Ocalan’s every move. The Mossad, Israel’s national intelligence agency, Israel was drawn into the saga following a phone call that Turkey’s Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit made to his Israeli counterpart Benjamin Netanyahu, asking for help in tracking Ocalan. Turkey, one of the few democracies in the Near East, was then a key ally of Israel, and Mr Netanyahu quickly agreed to help them capture Ocalan as long as the Turkish secret services would agree to claim all credit for his arrest and keep the Mossad role secret.

The then head of the Mossad Efraim Halevy was briefed by Mr Netanyahu and assigned a team of six agents for the operation. The effort was given the codename ‘‘Watchful’’. The search began in Rome. Six agents, including two technicians (yahalomin as they are known in Mossad circles) and a bat leveyha (female agent) set up a surveillance centre near Ocalan’s apartment not far from the Vatican.

The female agent’s brief was to attempt to make contact with the fugitive. But Ocalan abruptly left Italy. The team followed him frantically to Spain, Morocco, Tunisia, Syria and Portugal where Ocalan kept turning up and leaving as fast as he had arrived after being denied asylum. A breakthrough came when a Dutch official told the Mossad chief in Amsterdam that Ocalan had taken a KLM flight to Nairobi.

On February 5, 1999, the ‘‘Watchful’’ team arrived at JKIA. They were in friendly territory. The Mossad and Kenya’s National Security Intelligence Service (NSIS) and its forerunner, the Special Branch, have always had a special relationship. Mossad routinely shares intelligence information with Kenya. Mossad is also allowed to operate a safe house in Nairobi and to work closely with Kenyan national security apparatus.

The Mossad team tracked down Ocalan to the Greek ambassador’s residence, presumably after sharing intelligence with the Americans. They kept the house under constant surveillance before a call from then Mossad head Halevy changed everything. He ordered the team to capture Ocalan as soon as possible. The team decided to infiltrate Ocalan’s security team by tracking down one of Ocalan’s bodyguards while he was having a drink near the Norfolk Hotel.

One of the agents approached him and spoke to him in fluent Kurdish to win his trust. The pair established a rapport and Ocalan’s bodyguard told the agent that Ocalan was increasingly uneasy because all his applications for asylum, including the most recent one to South Africa, had been rejected. The Mossad agents already knew this because they were intercepting all communication from the Greek embassy in Nairobi.

A few days later, the agent who had made friends with the Ocalan bodyguard was instructed to meet him and relay a message that his (Ocalan’s) life was in danger and he should leave the ambassador’s residence immediately. The pair of ‘‘Kurds’’ agreed that the best option was to smuggle Ocalan to the mountainous Kurdish region in the north of Iraq, where it would be difficult to capture Ocalan.

The Israeli made this suggestion because the intercepted phone calls at the embassy had indicated this as an option Ocalan was considering. When the deal was sealed to smuggle Ocalan out of the embassy, his days as a (relatively) free man were numbered. On February 14, 1999, a Falcon-900 executive jet arrived at Wilson Airport. The pilot indicated he had come to pick up a group of businessmen in Nairobi. Later that afternoon, a team of Kenyan intelligence operatives and Mossad agents went to the Greek ambassador’s house and surrounded it.

They knew Ocalan had packed up to leave for northern Iraq. But, according to a senior Kenyan intelligence official with knowledge of the operation who spoke on condition of anonymity, they did not wait for Ocalan to make his way out of the compound. They burst into the residence, arrested him and whisked him off to Wilson Airport in Nairobi.

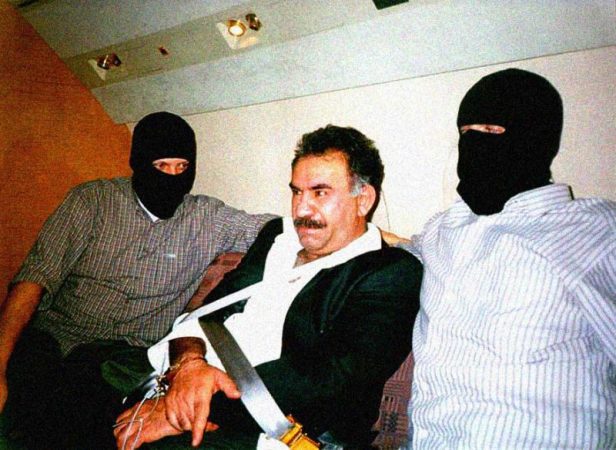

There, Ocalan was blindfolded, his fingerprints taken and faxed to authorities in the Israeli capital Tel Aviv and Ankara, Turkey. The drama was only beginning. Kenyan authorities had agreed to cooperate on the capture of Ocalan apparently without understanding the diplomatic crisis his arrest would trigger.

Over 12 million Kurds, among whom Ocalan enjoys almost messianic status, were outraged. Kenyan embassies in Europe were quickly surrounded by protesting mobs. Two officials at the Kenyan Embassy in Paris were kidnapped and later released. Three protesters were shot dead in the chaos. The situation was not helped when Ocalan, apparently unaware of Mossad’s role in his capture, placed the blame squarely on Kenyan authorities.

With the crisis getting out of control, Dr Godana the then Kenyan Foreign Affairs Minister issued an order shutting down all Kenya’s 34 embassies abroad.

Then the questions began. How had Kenya allowed Ocalan into its territory? Had money changed hands between the agencies which helped to capture Ocalan and Kenyan authorities? A report by the French news agency AFP alleged Dr Godana, appreciating the possible consequences of Ocalan’s capture, had opposed the decision to authorise his capture but had been overruled by President Moi.

Greece was equally embarrassed. It was quick to distance itself from the arrest of Ocalan, saying it had no role in handing him over to his captors. Facing hostile questioning from Kenyan authorities, George Costoulas, the country’s ambassador at the time, retreated to the country’s embassy on the 13th floor of Nation Centre and did not leave for three days.

Kenya demanded that he be recalled to Greece, a senior Greek government official Pavlos Apostolidis arrived in the country to apologise. He said the country had referred Ocalan to Kenya because they thought the “situation in Kenya was better… In the final analysis our decision to send Ocalan to Kenya did as much harm to Greece as it would have done if he had been in Greece.” As expected, the mood in Turkey was one of celebration. Then Prime Minister Costas Simitis, in keeping with his agreement with Mr Netanyahu, claimed credit for the capture and thanked the Turkish security forces.

Turkish newspapers lavished praise on their security forces and published detailed accounts of what they thought had happened. “When a Turkish officer grabbed his wrist and said ‘You’ve come to the end of the road, we are going to Turkey, Apo froze in horror,” reported the Sabah daily. Details of Mossad’s role would only emerge later. But Ocalan is unlikely to leave the remote Turkish island prison where he is serving his life sentence any time soon.

INSIDE THE GREEK INTELLIGENCE SERVICE MISSION THAT RESULTED IN OCALAN’S CAPTURE

A Greek insider version of the circumstances surrounding the arrest appeared in the international press. It stated:

Fiasco in Nairobi

In 1999 Greece’s National Intelligence Agency (EYP) conducted a high-risk operation that ended in a debacle and strained its relations with the United States, Turkey, and other nations. The operation was an effort to transfer Abdullah Ocalan, the fugitive founding leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), from Greece to a country in Africa to avoid his capture by Turkish authorities. Athens’s plan was to hide Ocalan in the Greek embassy in Nairobi until he could be transferred to another location. Army Major Savvas Kalenteridis, an EYP officer, was assigned to escort Ocalan to his destination. Instead, his actions in Nairobi not only failed to keep Ocalan from his pursuers but led to an international flap and ended several careers, eventually including his own. In the process, the Greeks exposed the ineffectiveness of their intelligence apparatus, which violated numerous fundamentals of intelligence tradecraft.

This account of events was compiled from press reports, leaked official Greek government documents, testimony given during a trial in 2003 of those who illegally brought Ocalan into Greece in 1999 and precipitated this misadventure.

The Greek Intelligence Mission

Ocalan’s secret and unsanctioned arrival in Greece set off a scramble in the Greek government, which sought to avoid the regional and international repercussions of harboring Turkey’s most wanted fugitive before knowledge of his presence became public. To deal with him, the government called on the EYP. After quickly contemplating several scenarios, Athens decided to fly Ocalan and his aides, escorted by intelligence officer Savvas Kalenteridis, to Kenya and then on to South Africa, where it hoped to negotiate asylum for him.

The Greek-registered Falcon jet carrying the Ocalan group, including Kalenteridis, landed in Nairobi at 1100 on 2 February. The day before, Vassilis Papaioanou, a senior aide to Foreign Minister Theodoros Pangalos, had informed the secretary of the embassy in Nairobi that the Falcon would arrive with important passengers. On the following day the passengers arrived—Ocalan traveling with a falsified passport with the name of a prominent Cypriot journalist, and alleged PKK sympathizer, Lazaros Mavros. On its arrival, the group was taken to the residence of Ambassador Georgios Costoulas.

The following day, Papaioanou called again, this time to inform Ambassador Costoulas that from then on any communication with the foreign minister’s office could only be conducted by telephone. At this point, Kalenteridis revealed his government’s complete plan. He explained that his orders were to depart for South Africa as soon as possible to make arrangements for Ocalan’s asylum and to obtain a valid passport for him. Ocalan was to remain in the custody of the embassy until the arrangements were complete.

A busy Thursday, the 4th, began with a early call from an officer of the US embassy in Nairobi seeking to arrange a meeting with the ambassador on Friday. Soon after, Costoulas was summoned to the Kenyan Foreign Ministry where he was questioned about the Falcon and its passengers. At about the same time, Kenyan authorities in Nairobi’s airport detained and questioned Kalenteridis, who was about to board a flight to South Africa. Forced to miss his flight, Kalenteridis returned to the official residence.

On Friday, the 5th, the Kenyan government intensified its queries about the passengers of the Falcon. A nervous Costoulas called back to Athens for instructions, and Papaioanou told him to “act like a shepherd and whistle indifferently” to the questions of the Kenyan authorities. Later on that same day, Papaioanou switched gears and instructed the ambassador to tell Ocalan that “he needs to be removed from the national [Greek] colors.”

When the ambassador asked where Ocalan should go, Papaioanou told him “The big singer [Pangalos] is upset. We did a favor. They shouldn’t make us regret it. Tell him to go on a safari. Tell him to go wherever he likes. He should stay away from [our] national colors.” When Costoulas and Kalenteridis suggested transferring Ocalan to a UN building in Nairobi, where he could ask for asylum, Papaioanou rebuffed them and continued to insist on Ocalan’s removal from “national colors.”

Citing fear for his life, Ocalan, rejected the eviction order and instead filed a written request for political asylum with the Greek government. As the pressure from Athens for his removal intensified, the women Ocalan had brought with him threatened to set themselves on fire in the embassy garden. Cowed, embassy members contemplated alternative escape scenarios over the next few days.

“Tell him to go on a safari. Tell him to go wherever he likes. He should stay away from [Greek] national colors.”

The standoff continued into Friday, 12 February, when it became clear that Kalenteridis was not helping his government’s cause. On that day, the chief of EYP, Haralambos Stavrakakis, called Kalenteridis and pleaded with him to kick Ocalan out of the residence: “Tell him to get out right away and to go wherever he wants. We didn’t promise him anything. Kick him out, Savvas, so we can finish with this. I am begging you, my child!” Kalenteridis refused the order.

The next day, Ocalan’s Greek lawyer arrived in Nairobi. Ocalan still had no valid passport and no fresh plans for departure to a new destination. After consulting with his lawyer, Ocalan insisted, unsuccessfully, that even if Greece rejected his application for asylum, the Greek government had an obligation to prosecute him in accordance with international law.

Again, Stavrakakis called Kalenteridis and ordered him to remove Ocalan from the embassy, by force if necessary. Kalenteridis again refused, saying he could not do it for practical reasons. Not long after, Kalenteridis received still another call from EYP headquarters, this time from someone by the name of Michalis. “Savvas listen to me, I am Tzovaras and present are three ministers and the chief. The careers of three ministers are on the line because of your actions, do you understand that? You should go and remove him [Ocalan] by force at once.”

“The careers of three ministers are on the line because of your actions, do you understand that? You should go and remove him [Ocalan] by force at once.”

Kalenteridis refused yet again, saying he was unable to use force. Tzovaras continued to plead with him. “I am begging you, Savvas, throw him out so we can finish with this. You can do this. Be careful, because if you don’t do this when you come back they will discharge you. You can do this. There are three ministers here…”

Kalenteridis, unmoved, refused again, his fourth refusal into the mission. Only then did the government in Athens decide to dispatch a four-member EYP security team to enforce its orders. This development was conveyed to Ambassador Costoulas by the EYP and Papaioanou at the Foreign Ministry, who informed him that a “theatrical group, a football team” would be arriving the next day, which if necessary “will play ball.”

On Sunday, the 14th, at 1300, the security team reached the residence, having been briefly detained and questioned by Kenyan authorities at the airport. The agents realized they were under surveillance by Kenyan and other foreign agents. A couple of hours before the EYP officers arrived at the Greek embassy, the secretary of the embassy received a call from Papaioanou at the Foreign Ministry, who asked him to take detailed notes as he provided new directions. These, he warned, were to be followed to the letter:

The “football team” will have instructions to act fast, and if necessary by force. The grandmother (Ocalan) is to be removed immediately. A room for him should be booked at a local hotel.

He was to be given a little bit of money if necessary. He was to be taken to a location near the hotel, even if wrapped in a bedsheet. He and his associates were to be abandoned and any communication with him ended at that point. Everything had to be finished by Monday, the next day.

And finished it was, but apparently not as the Greeks had intended—at least not as Kalenteridis had intended. On Monday, 15 February, Costoulas was summoned to the Kenyan Foreign Ministry and told that the Kenyan government knew Ocalan was hiding at the residence. Costoulas was offered an aircraft for a swift departure to a country of Ocalan’s choosing. Contacted, Foreign Minister Pangalos accepted the Kenyan offer and agreed to remove Ocalan within the two-hour window the Kenyans provided.

Athens asked for details about the aircraft and its flight plan but was rebuffed. The Kenyan government also refused to permit the Greeks to use their embassy car—sovereign territory—to take Ocalan to the airport, insisting instead that Kenyan government cars be used. After intense negotiations in the embassy, Ocalan boarded a Kenyan government vehicle—without his aides and without any Greek official. He was driven to the airport and placed on a waiting plane, where Turkish agents seized, shackled, gagged, and blindfolded him. He was returned to Turkey and put on trial that year.

What went wrong for the Greeks?

Whatever the political foundations of the decision to take Ocalan to Kenya, Athens’ neglected important operational considerations, dooming the effort virtually from the start.

The objectives of the EYP’s mission were clear enough:

Kalenteridis and his team were to take Ocalan to a temporary secure location outside of Greece from which Ocalan could find permanent refuge elsewhere. The mission was to proceed in a way that no other country would know that Greece was harboring and helping Ocalan.

Ocalan was to be protected from any agents seeking to seize him and transfer him to Turkey.

Those objectives would fall victim to international pressure, as we have seen, but in all probability the operation was compromised very soon after it began, and the Greeks should have known it.

Athens’ neglect of important operational considerations doomed the effort virtually from the start.

The decision to take Ocalan to Kenya was a poor one. As the theater in which this operation was to be carried out, Kenya was inappropriate for several reasons, the most important of which was the fact that just less than six months before, the US embassy there had been bombed by al Qa’ida, and numerous US officials were likely to have been investigating the scene. In addition, Kenyan authorities would most likely have been on high alert and, even if they were not, they were unlikely to have been helpful in any effort that might have implied support for a declared terrorist like Ocalan.

According to EYP chief Stavrakakis, Foreign Minister Pangalos initially wanted to transfer Ocalan to Holland, but the attempt failed because Dutch authorities refused landing rights because a large crowd of Kurds had gathered at the airport. Pangalos later claimed that the EYP had suggested Kenya as a way station while negotiations with South Africa took place. Given the circumstances in Nairobi and the many alternative locations around the world housing Greek diplomatic facilities, the EYP’s choice is puzzling.

The tradecraft of the EYP and other components of the Greek government were exceedingly lax. Members of the organization paid inadequate attention to communications security, counterintelligence, protection of sources and methods, as well as threats to the security of the personnel involved in the mission.

Given the Dutch experience, conditions in the Kenya, and the intense interest in Ocalan around the world, there was every reason to believe Ocalan’s movements were being tracked. Leaked documents indicate that both the Turkish and US governments knew Ocalan was in Greece and knew when he was transferred to Kenya. The documents show that the Turkish embassy in Athens made an inquiry to the Greek Foreign Ministry while Ocalan was still in Athens; in addition, the request of the US embassy in Kenya for a meeting with ambassador mentioned above also implied knowledge of the situation.

Embassy communications practices most likely contributed to compromises. The most critical field communications of the operation, specifically from EYP headquarters in Athens, took place entirely by telephone—even payphones. Codenames like “grandmother” (Ocalan), “big singer” (Pangalos), and “football team” (team of intelligence officers) were inadequate to provide a layer of security to communications. Moreover, not everyone was addressed with a codename. The lead field agent, Kalenteridis, was always addressed by his given name, according to the leaked documents.

Finally, the physical security of Ocalan, his aides, and the escorting team was inadequate. As Stavrakakis later noted, the Public Order Ministry had provided too few security personnel for the mission, even leaving them unarmed.

Kalenteridis’s selection to head the Ocalan mission brought distinct advantages… At the same time, there should have been suspicions about his suitability for

the sensitive mission.

The chain of command was broken as senior officials of ministry rank became intimately involved in the operation. Testimony during the 2003 trial and leaked Greek government reports make clear that ministerial rank officials were involved in the macro- and micro-management of the operation. Such breakdowns in the routine chain of command can signal failings in authority above; create uncertainty in the field; and permit, or force, field operators to question and even challenge their orders, especially when a core mission has changed so clearly and rapidly.

After involving itself in Ocalan’s relocation, selection of Kalenteridis to lead the mission was the Greeks’ most critical error. A qualified selection to head an autonomous operation such as this one would ideally have the knowledge and expertise appropriate to the nature and location of the mission. These include fluency in specific foreign languages, knowledge of specific cultures and locations, and so on. These, on the surface at least, Kalenteridis had.

Kalenteridis was born in 1960 in the small town of Vergi near the northern Greek city of Serres. His family had its origins in an ethnic Greek community on the Black Sea, known to Greeks as Euxeinos Pontos (Hospitable Sea). Like most Greeks whose families were repatriated from faraway places, Kalenteridis was raised to respect, admire, and honor Greece’s history and heritage. Vergi is a historical one, home to several ancient ruins of the archaic era (800–500 BCE). Moreover, the town is not far from Greece’s northern border with Bulgaria, an area that traditionally has had strong nationalist sentiments.

Kalenteridis excelled in school, and in 1977 his high marks earned him entrance to the Evelpidon Military Academy, Greece’s top military academy. Kalenteridis graduated in 1981 with the rank of second lieutenant. He went on to serve in several tank and paratroop units in Greece and in posts abroad. At one time he was a military attaché in Izmir, Turkey. His fluency in Turkish and knowledge of foreign affairs made him an asset to the National Intelligence Agency, for which Kalenteridis worked covertly for several years, mainly in Turkey.

Kalenteridis’s selection to head the Ocalan mission brought distinct advantages: his expertise in Turkish affairs, his fluency in the language, and his knowledge from past service as an EYP agent in Turkey. At the same time, there should have been suspicions about his suitability for the sensitive mission.

First, his superiors might have considered his family’s roots and the tradition of nationalism it implied, even if Kalenteridis himself had never expressed them openly.[6] More pointedly, EYP officials later revealed they knew that in December 1998, just a month before Ocalan arrived, Kalenteridis had been in Rome acting as the interpreter in a meeting Ocalan had with Panagiotis Sgouridis, a vice chairman of the Greek Parliament. The task apparently had not been assigned or sanctioned by the EYP.

During the same period, EYP chief Stavrakakis received a tip that Ocalan might be brought to Greece in late January 1999. It was at that point, EYP Espionage Division Director Col. P. Kitsos told his superiors that he had concluded that a component of EYP was operating autonomously and that officers in that component were prone to disobey official government orders.

Athens may not have emerged unscathed from this episode even if Kalenteridis had done as he had been told. In the end, his refusals extended the problem

and magnified the

fiasco in Nairobi.

In this operation, Kalenteridis apparently overrode his government’s and his intelligence service’s interests—as the Greeks would say, “He was wearing two hats.” Kalenteridis has never publicly explained his position, but we know his obligations: He had taken an oath to serve and protect his country and it was not his position to pass judgment on the political, diplomatic, and intelligence matters that drove the changes in his mission. He should have obeyed his orders.

Athens may not have emerged unscathed from this episode even if Kalenteridis had done as he had been told. But in the end, his refusals extended the problem and magnified the fiasco

in Nairobi, led to the embarrassment of his government, added new strains in relations with Turkey and the United States, and fueled the wrath of Kurds worldwide.

Epilogue: Three cabinet members and the chief of the EYP resigned soon after Ocalan’s seizure. Kalenteridis would himself resign a year later. Ocalan was tried in 1999 in a Turkish court and sentenced to death. The penalty was reduced to life in prison in 2002 after Turkey abolished the death penalty. He has been serving his sentence in solitary confinement on the prison island of Imrali in the Sea of Marmara off northwestern Turkey.

Sources: Nation Media, CIA.gov