November 08, 2021

Nation Media Group

Across the length and breadth of the violence-prone Samburu County, evidence of murder is plentiful.

In the past two months, 24 people were killed by brazen bandits who seem to be more tactical than trained security officers, going by the manner in which they strike.

The most insecure areas are Marti, Mbukoi, Baragoi, Nachola, Suyian, Kawap, Nkoriche and South Horr in Samburu North. In Samburu East, you are most likely to die in Wamba, Lerata and Achers Post. Suguta Mar Mar, Longewan and Malaso are also dangerous.

On November 3, 14 people who had just retired after a long day in search of pasture, were rounded up and shot dead by a gang of about 50 cattle rustlers in Suyian village of Samburu North.

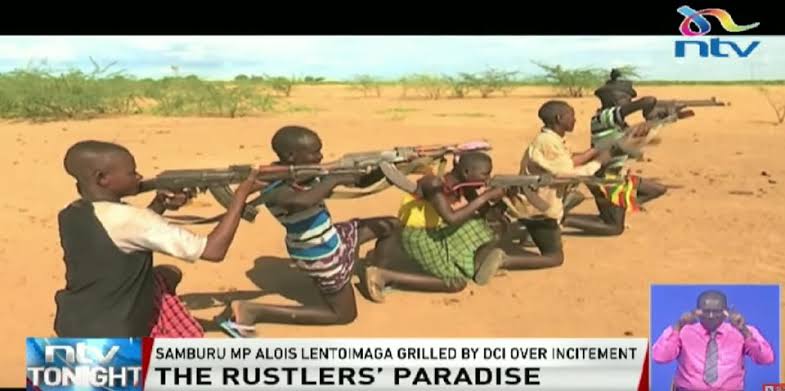

The ruthless raiders, armed with assault weapons, killed indiscriminately and did not even spare women and children; their mission was to leave no life behind before driving away with 1,000 heads of cattle.

Although they initially met some resistance from local Morans, they had way too powerful guns that silenced the opposition. In the end, they left a trail of death with surrounding villages devastated and traumatised.

Local residents were so outraged that they called upon authorities to show up and witness the tragedy that had befallen their community. Yet, this is the routine in a region that bandits and rustlers rule with the gun.

Brazen bandits

Across the length and breadth of the violence-prone Samburu County, evidence of murder is plentiful. In the past two months, 24 people were killed by brazen bandits who seem to be more tactical than trained security officers, going by the manner in which they strike.

The most insecure areas are Marti, Mbukoi, Baragoi, Nachola, Suyian, Kawap, Nkoriche and South Horr in Samburu North. In Samburu East, you are most likely to die in Wamba, Lerata and Achers Post. Suguta Mar Mar, Longewan and Malaso are also dangerous.

Fear, tension and hopelessness is a way of life in this theatre of death. The bandits strike any time, day or night, and don’t fear security agencies because they are better armed. Some even carry special military weapons used by elite forces. How they get them remains a puzzle.

Several policemen posted to the axis of violence to combat the attackers have also fallen victim, and died in the line of duty. The security situation in Samburu is proving intractable despite the government’s repeated assurances that there are enough boots on the ground.

To an outsider, Samburu is a marvellous county whose landscape has wonderful plains and perfect hills and valleys that define beauty. From Samburu Central to Baragoi, it’s a couple’s paradise.

Beneath beauty lies wanton killing

But beneath that beauty, beneath that paradise, lies death and destruction. The wanton killing of innocent villagers in endless cattle raids is a clear affirmation of the reality locals live with.

“These bandits strike any time and we are helpless, knowing that death can knock at any time. We have lost our cattle, but every time the government only gives threats and life moves on. We are being hunted down like rabbits,” says Mr James Lekandero, a resident of Baragoi.

Mr Stephen Leekete, a Moran, says they have resorted to use their firearms to protect themselves. “Death stalks us here. All because of the bandits. It seems the government has surrendered,” he offers.

Last month, three people were killed, three children injured and over 500 livestock stolen after bandits attacked Lporokwai village in Porro location. The bandits shot dead a father and his son, who were herding their livestock before they drove away the animals.

Police, who later recovered over 50 goats, are yet to arrest the culprits. On July 19, two people were killed when suspected armed cattle rustlers raided Marti in Samburu North and stole 521 animals.

The attack came barely three days after armed rustlers raided the same village and stole more than 200 goats. No arrests were made and no animals were recovered.

On October 15, police in Samburu recovered two assault rifles with rounds of ammunition in Parikati area following a failed cattle raid. The two firearms – AK-47 and FN FAL – with 20 and 14 rounds of ammunition, respectively, were recovered when police responded to an attack.

Samburu County police commandant Samson Ogelo says one ranger was killed following a gunfight with bandits. The incident came two days after a suspected cattle rustler was killed by police and an M16 rifle with 25 rounds of ammunition recovered.

On November 24 last year, two people were killed while another was injured in two separate attacks in Baragoi town. A nine-year-old boy died on the spot after he was shot on the chest by armed bandits while herding livestock at Natiti area at around 11am.

A few hours later, a boda boda rider and his pillion passenger were sprayed with bullets. The rider died while the passenger sustained a bullet wound on her shoulder.

Samburu Woman Rep Maison Leshoomo says deployment of police reservists to the region will help end the attacks. She has also urged the national government to find a long-term solution to cattle theft.

“We need to end the continuous mourning of our people because of few criminal elements. Security organs should intervene,” she says.

In 2019, the government disarmed reservists on the grounds that they were behind the insecurity. Ms Leshoomo now wants the Interior ministry to reinstate them because they understand the terrain well and can respond to bandits better than the police.

Rift Valley regional coordinator George Natembeya says bandits carry sophisticated firearms and often outgun elite security forces, including the Anti-Stock Theft Unit and the General Service Unit.

“While our officers are using AK-47s and G3 rifles, they have M16s and other heavy assault weapons, which are usually used by the military in foreign countries. We don’t know how they get these weapons, but it is an issue under investigation,” he observes.

Independent investigations by the Nation show that the illicit weapons come from several sources, including the Ethiopian rebel group, Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).

Many are smuggled into the country through the porous borders from Ethiopia, Uganda, Somalia and Sudan.

“One of the M16 rifles recovered from bandits last month had a sticker of an Ethiopian flag. It was manufactured in the US,” says a police source.

Commercialisation and politicisation of rustling

Security experts also say cattle raids have turned deadly due to their commercialisation and politicisation. Mr Kiyo Ng’ang’a says the solution is sealing the porous borders.

“Disarmament won’t help; the government must endeavour to stop smuggling of the illegal firearms from other countries,” he notes.

The government claims some politicians supply the guns to bandits.

Interior Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang’i says the government has deployed more security officers to Samburu and Marsabit to tackle the rising insecurity.

“We have deployed more security officers to the affected areas and I urge local leaders to talk to the locals and tell them that killing each other is not a solution. Turning guns against each other won’t help. The communities need to live and co-exist in peace,” he offers.

Police spokesperson Bruno Shioso says a major security operation is under way in the region.

“A contingent of security personnel drawn from the GSU is already on the ground going after the bandits to recover stolen animals. Security around the affected areas has been beefed up,” he notes.

“To end the problem, we have approached it in three ways: We have enhanced security, embraced peace-building initiatives through administration and local committees, and direct resource support including infrastructure improvement to open.”

Successive governments have issued edicts against bandits, yet none has had the capacity to end it. It remains to be seen if the Jubilee administration will succeed in ending insecurity here.

A walk in the shadow of the valley of death and horror

November 17, 2012

Nation Media Group

Suguta Valley in Kenya’s northern county of Samburu gives a horrible appearance from the sky. It looks like a sick human skin, with rocky hills standing out as wounds.

A dry river bed snakes through these hills, and joins a thorny area over the horizon with no sign of humanity. The midmorning sweltering heat makes you feel like you are passing through a furnace.

Mr Julius Lampasia, 52, a resident sums it up as follows: “To live here, you must be strong. It is hot, no water. We have our neighbours too, with whom we have lived for years fighting. We are forgotten.”

Situated about 500 kilometres North West of Nairobi, the neighbouring Lomeruk village looks like ring worm infections, standing out from far but very amorphous. Here, villagers left as soon as they heard the government had declared war on bandits.

The rustlers felled a group of policemen pursuing them for livestock they had stolen from a Samburu village, some 13 kilometres north east in Baragoi. Now another set of police officers have been left to look for the bodies of their colleagues.

They are combing the valley, being led by the smell of rotting flesh of their departed colleagues, killed in line of duty, six days earlier.

It is difficult for them, but they swore to serve this country, regardless of the dangers involved. Their chopper hovers southwards searching for more bodies.

There is none, but a herd of cattle is spotted driving further through the valley. No human can be spotted though.

The valley is like dead quarry, yet it continues to bite at human life. Here, people enter, but hardly return. There is no mobile phone signal, no clear track to escape through and even if you screamed, it would echo on the walls of the valley.

It has claimed many lives, including those of District Commissioner James Nyandoro, soldiers and now 42 police officers.

The only signs of the recent attack are scattered pieces of remains and combat uniforms. A hat and a handkerchief here, a boot there.

Bodies have been partly feasted upon by wild animals as maggots get their feel. One of the bodies is missing a limb while the other leg looks twisted backwards as though some animal tried to break it off and dash with it.

Another has no head, and it makes it difficult for the rescue team here to identify it.

“I have been here since Monday, am looking for my in-law who was an officer with the Anti-Stock Theft Unit. I still haven’t seen him,” laments Hussein Goso from Marsabit.

But it is their death that might have been painful. Having pursued the more than 300 rustlers making away with the livestock from the manyatta, a member of the rescue team claims, the officers were duped through the valley as their targets rushed with the animals to a hill.

Then they started shooting back while still driving the animals beyond the hill. The officers got overwhelmed and started to retreat. They had been ringed! They fell into another group of bandits who shot those withdrawing.

Here, it is the rule of the jungle where to survive, you have to hold onto that gun, and aim at the target regardless of whether the gun is legal or not. If you can’t, then you have to flee fast. And if you are killed, you become a meal for the scavengers roaming the valley.

“There are wild animals like hyenas which can attack you. But most often they eat the dead,” adds Mr Lampasia, the father of 14. He says he lost two of his sons to rustlers.

The village is like a ghost town, fenced with dry thorny twigs with at least eight gates, each opened and closed with a single cut thorny branch of acacia. The manyatta was occupied by the Turkana, suspected to have masterminded the ambush on police officers.

Each of the gates has a fox hole nearby, where guards might have hidden, ready for war. As you enter, a couple of quails fly away as flames lick away dry dung, perhaps a sure sign that they were livestock keepers.

You have to admire the artistic ability of these people in weaving sticks together for walls, then gluing it with fresh dung.

No one knows how they survived when it rained. The place is flat but their roofs are made from mosquito nets, some from old cartons, and others from woven sticks still.