Nation Media Group

December 01, 2018

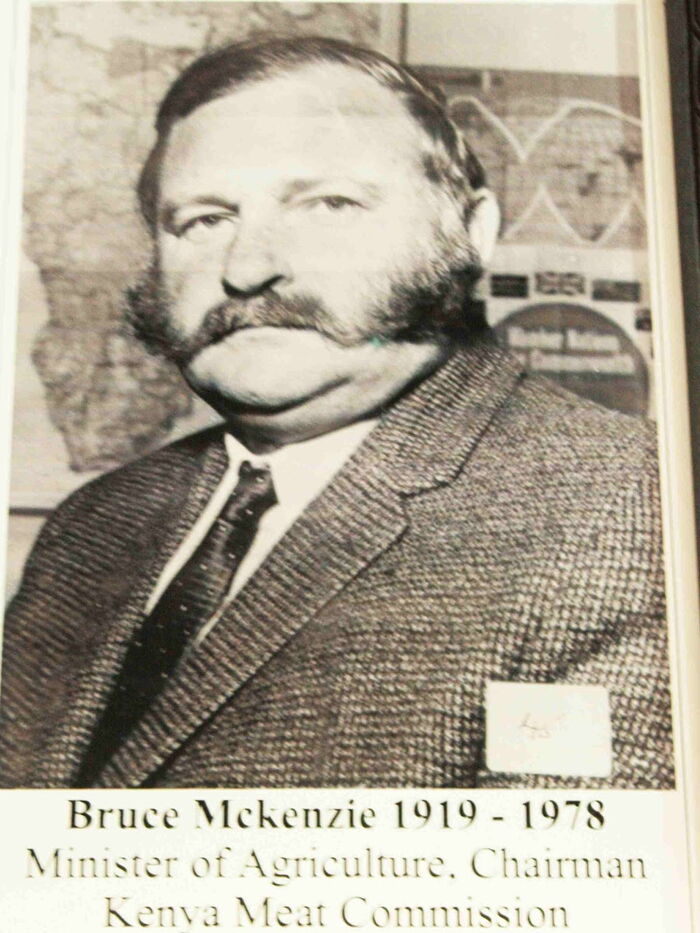

Editor Joseph Odindo and I were the first local journalists to tell the story of Bruce McKenzie’s double life as a Kenyan cabinet minister and nominated MP, but also a secret agent of the British intelligence outfit, MI6, the Israel spy agency Mossad, and the apartheid South Africa Bureau of State Security (BOSS).

We published the story in the Echo magazine which has since folded, and later as a four-part series in the Daily Nation.

Our story only touched on McKenzie’s activities inside Kenya, which included the Nairobi connection in the famous Entebbe hostage rescue in Uganda that became stuff of international blockbuster movies. His other exploits in the shadowy world of espionage extended to Uganda, Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia), and South Africa.

When white settlers in colonial Zimbabwe unilaterally declared independence from Britain, McKenzie had proposed they be punished by secretly introducing an untreatable streak of anthrax to wipe out cattle in the colony, which at the time was the country’s economic lifeline.

HAROLD WILSON

McKenzie’s most sensational assignment outside our soil is perhaps his role in the intrigues that led to the downfall of British Prime Minister Harold Wilson in April 1976.

South African born McKenzie and a former pilot with British Air Force settled in Kenya after World War II to do extensive farming at Solai near Nakuru town.

The extensive farm he owned has since changed hands to the family of retired President Mwai Kibaki who are now developing it into a giant real estate venture.

Towards independence, McKenzie had dabbled into politics joining the Kenya African Democratic Union before hopping onto Kenya African National Union.

There he gained quick trust of the Prime Minister and later first President Mzee Kenyatta who appointed him independent Kenya’s first Agriculture minister.

LAND TRANSFER

He was to play a leading role in the successful but controversial land transfer from the white settlers to Africans at independence.

He resigned as Cabinet minister six years later to concentrate on what he called “personal pursuits” but remained a nominated MP.

He wouldn’t appear in Parliament for as long as eight months but still got away with it, thanks to his good connections where it mattered.

But wherever he was, in or outside government, McKenzie’s influence remained deep to an extent a Nigerian political commentator, Prof Zeeky Rukari, in a paper entitled “Who rules Kenya?” described him as “the leader of the invisible government.”

FRIENDLY LIAISONS

Did the Kenyan authorities know McKenzie to be an agent of foreign spy agents and at what point? Also were his secret liaisons harmful to the country’s best interests?

When I first put the question to Geoffrey Kareithi, a long-serving Head of Civil Service and Secretary to the Cabinet in Mzee Kenyatta’s government, in the 1990s, he categorically denied McKenzie was a spy and dismissed it as a conspiracy theory by international media and espionage writers.

At the time Kareithi was an assistant minister in President Daniel Moi’s administration, perhaps tied by the usual bureaucratic stone-walling and tendency to deny even the plain obvious.

Much later when I met a retired and aged Kareithi, he readily admitted that the Kenya government was aware of McKenzie’s “clandestine connections” but didn’t mind because they were not harmful to Kenya’s interests.

He told me that except for the apartheid South Africa, Britain and Israel had, then as now, deep intelligence partnership with Kenya on matters of mutual interest like counter-terrorism and in blocking communist influence, a major preoccupation of Western spy agents in the cold war era.

FREQUENT VISITORS

He disclosed that Kenyan authorities knew one of McKenzie’s frequent visitors in Nairobi to have been then head of the British intelligence unit MI6, Sir Maurice Oldfield.

The latter would sneak in and out of Kenya “black”, which is the intelligence term to mean without going through mandatory checks at the airport.

Kareithi, too, revealed that when McKenzie died, Kenyan authorities secretly facilitated travel to Israel by his widow for a function to honour her late husband organised by the Mossad, an indication of how valuable the Kenyan was to the spy agency.

In the book: British Intelligence and Covert Action, British first High Commissioner to independent Kenya, Sir Malcolm McDonald, is quoted as saying McKenzie was recruited by the MI6, just before or immediately after Kenya’s independence.

He says McKenzie was brought on board by one David Stirling, a fellow officer in the British military during the World War and who had since been engaged by the MI6 to befriend leaders in the former British colonies.

MI6 OPERATIVE

McKenzie must have been a good catch given his friendship with President Kenyatta, and the fact that he sat in the Kenya cabinet and parliament.

Recruited with McKenzie was one George Young, another MI6 operative privy to machinations leading to Prime Minister Wilson’s fall from grace.

Kareithi told me MI6, in turn, could have introduced McKenzie to the Mossad in the spirit of what is called brotherhood of intelligence. The South Africans didn’t need any introduction as it was McKenzie’s country of origin.

In the period 1973/74, Britain was a country in turmoil, fuelled partly by the global oil crisis, and an unprecedented labour unrest at home. The miners had downed tools almost bringing the country’s industrial jugular to a standstill.

Never since the World War 2 had Britain got to such low that cynic commentators mocked that there was no longer anything “great” in Great Britain and nothing “united” in United Kingdom.

DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE

British domestic intelligence arm, the MI5, as well as the American CIA highly suspected the Russian intelligence, the KGB, to be the secret hand behind the labour unrest in Britain, working in cahoots with the opposition British Labour Party which tacitly supported the miners’ strike.

Rumours were awash in London that the leader of the Labour Party Harold Wilson, then campaigning to oust Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, and up to 50 Labour MPs secretly worked with the Russians to sabotage the Conservative government.

Subsequently, the British intelligence, egged on by the CIA, were determined that the Labour Party mustn’t win the Prime Minister elections scheduled for February 1974.

Enemy at Number 10: Enter McKenzie.

Suddenly whispers spread that having Labour leader Harold Wilson elected Prime Minister would be tantamount to having the enemy take over at Number 10 Downing Street, the London address of the prime minister’s office.

COMMUNIST PENETRATION

There was also talk of “the Reds under the beds”, a scare line to exaggerate the extent of the communist penetration in Her Majesty’s country.

Leading espionage writer, Chapman Pincher, would later reveal that Labour candidate Wilson and other top officials in his party were on active surveillance of the MI5 and the American CIA. Part of the strategy was to gather as much dirt on individual candidates in the Labour Party and pass it to the rivals in the Conservative Party.

According to Pincher, as soon as the secret dossier was ready, it was passed to chairman of the ruling Conservative party, Lord Carrington, for onward transmission to Prime Minister Edward Heath. But the latter, discloses author Pincher, wasn’t interested arguing that he was sure to defeat the Labour candidate and didn’t want to have been seen to have used dirty tricks to do so.

But with the intelligence community determined not to leave any chance, a new channel had to be found to have the Prime Minister change his mind.

DIRTY TRICKS

McKenzie came in handy. He happened to be friend of one Lord Aldington who, in turn, was a friend of the Prime Minister. Lord Aldington, who was chairman of a merchant bank in London, happened to have served in the military with McKenzie.

In later life, he would come in handy to do a favour or two for McKenzie’s clients in the world of espionage. According to Pincher, the Prime Minister remained adamant not to use the anti-Labour dossier supplied by the MI5 insisting he was sure to win without resorting to dirty tricks. But he lost the election to give McKenzie and his friends a chance to say: “See now what has happened after you refused to listen to us!”

With Harold Wilson, the “enemy” now sitting at the No 10 Downing Street, efforts to sabotage and bring him down went a notch higher.

An opportunity for a showdown and which roped in McKenzie didn’t take long in coming.

CIVILIAN REGIME

Early in his administration, a military dictator, Augusto Pinochet, with the help of the CIA, overthrew the civilian regime in the South American republic of Chile. It was an ironic madness of the Cold War era that Americans would rather have a ruthless dictator in power and not a fairly democratic civilian administration sympathetic to communism.

A radical wing in the British Labour party came out in the open to oppose the new military junta in Chile and urged Prime Minister Wilson to impose a trade embargo.

Alarmed that Wilson might be pressured to act, the CIA and the MI5 prevailed on him to not only decline the wishes of the radical wing in his party, but push it to the periphery where it wouldn’t have influence on his administration.

To put pressure on the Prime Minister, British intelligence embarked on a media smear campaign against the radicals in Labour party.

According to author Pincher, it’s to McKenzie and his old friend, George Young, to whom MI6 director, Sir Maurice Oldfield, turned to spearhead the smear media campaign on radicals in Wilson party.

ABRUPT RESIGNATION

Eventually, the Intelligence turned its guns on the person of the Prime Minister Wilson. According to writer Pincher, a few months to the Prime Minister’s abrupt resignation, McKenzie had tipped him that the Prime Minister had established beyond doubt that British Intelligence had secretly bugged his office and the cabinet room. McKenzie, in turn, had been told as much by none other than his friend and frequent visitor in Nairobi, MI6 director Sir Maurice Oldfield.

In the book “Web of Deception” Pincher describes McKenzie as “an extra-ordinarily well informed Kenyan politician and close friend of Sir Maurice Oldfield.” Pincher lived in a London neighbourhood where McKenzie owned a flat.

Last word: Under pressure from the House of Commons and the British media, Wilson’s successor as Prime Minister, James Callaghan, ordered an inquiry into allegations of secret bugging and eavesdropping on his predecessor.

STRANGE DEVICE

The report of the inquiry headed by his cabinet secretary Sir John Hunt was never made public. However, a leak in the British media would have it that the inquiry established that a “strange” device had been retrieved from the cabinet room.

According to the 30-year rule on release of records at the British Public Records Office, the report of the inquiry was due for release in August 2008.

But a quick check online indicates no such report has ever been released. If and when it is available, it perhaps shall finally shed light on the issue of “enemy at No 10”, and probably include a sentence or two about “our own” Bruce McKenzie.

Story of Idi Amin’s adviser Bob Astles, Bruce McKenzie’s murder

Nation Media Group

May 25, 2019

It is 41 years this weekend since the death of Bruce McKenzie after his twin-engine Piper Aztec 23 plane exploded over Ngong Hills, a few minutes after 6pm on May 25, 1978 as he flew back from a meeting with President Idi Amin of Uganda.

It was an assassination, nay, murder at sunset.

For starters, McKenzie was the only colonial-era Cabinet minister retained by President Jomo Kenyatta after independence, and he was until 1969 Kenya’s minister for Agriculture – while also helping many of his fellow Cabinet ministers enter into business and, like him, become millionaires.

McKenzie was not your ordinary soul. He was an astute wheeler-dealer, politician, spy and ‘Mr Fix It’. He had enemies, too. Terrible, uncanny and ruthless, just like him.

The identity of who planted the time bomb that killed McKenzie has always been speculated.

BOB ASTLES

For his part, President Amin tried to distance himself from plotting the death of McKenzie to retaliate the humiliation he faced after the Entebbe raid by Israeli soldiers on July 4, 1976 – as they rescued 103 passengers taken hostage when a French airliner was hijacked en route from Israel to France.

As to the suspected agent, one name keeps recurring: that of British-born Bob Astles, regarded as Idi Amin’s political adviser but who regarded himself as “odd-job man”.

He also told those who cared to listen that he was head of anti-corruption squad.

In Amin’s Uganda, odd jobs had no definition and ‘Mr Bob’ – as the man was known in Kampala – was left to interpret his job description.

He did it with gusto and those who crossed his path faced the wrath of Uganda’s State Research Bureau – a notorious spy network that operated from a three-storey building with an odd name: State Research Centre and headed by Major Farouk Minowa.

MIDDLEMAN

The moustached Bob Astles was the brains behind this “research centre” which he had helped set up in 1973, and its only equivalent, in terms of notoriety, was the infamous Makindye Military Police Barracks.

Astles had known McKenzie for years and his Cooper Motors Corporation had supplied the Land Rovers used by the Research Bureau; in effect, McKenzie was also a supplier to Amin’s murderous gangs.

After his retirement from the Cabinet, McKenzie had secured the Volkswagen dealership in East Africa with Charles Njonjo and was the middleman on purchase of Vickers tank by Kenya in 1976.

With this prowess, Amin, or rather Astles, had turned to McKenzie to deliver radio equipment to the secret police from UK’s Pye Telecommunication through its Kenyan distributor Wilken Telecommunications Limited.

This company was owned by McKenzie and Keith Savage and supplied Amin with VHF-FM radio telephone systems and Land Rovers ostensibly designed to “detect television licence dodgers”.

In 1976, another British company, Contact Radio and Telephone, had built a bullet-proof broadcasting station for Amin which could be used in times of war and emergency.

DOUBLE-DEALER

It was a booming business, and it is now known that both McKenzie and Savage made several trips on weekly basis to Uganda and held lengthy talks with Amin.

Whether this closeness to Amin scared Astles is not clear.

It is interesting that one of the passengers aboard the ill-fated flight was Gavin Whitelaw, a representative of Vickers – a British company that built battle tanks for export.

This led to speculation that McKenzie’s trip was possibly to secure an arms sales deal.

But McKenzie was a double-dealer, too. He is said to have persuaded Jomo Kenyatta to allow the Mossad to gather intelligence from Nairobi and to permit the Israeli Air force access to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, shortly after the Entebbe raid.

Whether this was known to operatives within Amin’s circle of political buffoons is not clear, although it is now well-documented in secret papers and through first hand testaments.

ASTLES’ REWARD

But in a message to Amin, after the death of McKenzie, his widow rejected the notion that the Ugandan dictator had been personally aware of the plan to kill Bruce.

“I feel that I can let you know that I, being his widow, utterly reject such irresponsible statements,” she wrote.

The McKenzie family did not want to antagonise Amin in order to protect their business fortunes.

It is now known that Astles called Nairobi asking whether the aircraft reached safely.

It is this call which led to speculation that Astles, and by extension Amin, was involved in the assassination.

“Some observers believe that McKenzie had been muscling in a ‘territory’ Astles considered his own,” said an US Cable quoting officials familiar with the matter.

So close was Amin to Astles that he had appointed his Ugandan wife, Mary Senkatoka, as a Cabinet minister.

But he was wary of any other foreigner who could get close to Amin. On top of his hit-list was McKenzie and Keith Savage who were business allies of Kenya’s attorney general, Charles Njonjo.

MOSSAD

In Uganda, Astles had few friends and expatriates and diplomats nickname him “the white rat” after he masterminded the kneeling of expatriates before Amin.

Amin was also carried into an Organisation of African Unity conference in Kampala on a chair by four expatriates.

It is claimed that after ‘Operation Thunderbolt’, Astles convinced Amin that these Kenyan-based businessmen were Mossad operatives (which could have been true).

It was after a meeting in Njonjo’s Muthaiga house that Kenya allowed Israeli fighter jets to land and refuel at JKIA.

British military historian and broadcaster Saul David, in his new book Operation Thunderbolt, says that Kenya’s involvement had to be kept top secret.

He claims that the country – without the knowledge of President Kenyatta – had provided a base for Mossad agents to gather intelligence on the Entebbe old terminal prior to the operation.

What we know is that Mossad director Yitzhak Khofi contacted Mackenzie who consulted with then-Home Affairs Undersecretary Nicholas Biwott, and they organised for a Mossad operative Shalomo Gal to charter the plane that photographed Entebbe augmenting intelligence.

ASSASSINATION

Michael Harari, another Mossad senior agent, also travelled to Uganda by disguising himself as an Italian businessman to gather more intelligence.

For that, and in McKenzie’s honour, former Mossad head Meir Amit had a forest planted in Galilee.

Amit is credited for helping Israel in forging ties with various African countries by preferring diplomatic pressure – secret or overt – to assassination.

He once wrote: “In intelligence, people are more important than rifles.”

Later on, Astles revealed that he knew of the plot to kill McKenzie but said that he had nothing to do with it.

He would also claim that he, too, was a victim of Amin’s murderous gangs and that he had twice been targeted.

ENEMIES

In the Kenya political circles, McKenzie was a friend to not only Njonjo but also health Minister James Osogo, Water Development’s Dr Gikonyo Kiano and later on Vice President Daniela arap Moi and Finance minister Mwai Kibaki, who later purchased McKenzie’s Gingalili Farm near Solai, Nakuru.

Some pundits still say that McKenzie was at the wrong place – with the wrong person, Keith Savage who had survived another assassination attempt a few weeks earlier in Nairobi.

According to American intelligence briefing, he had made a “great number of enemies here over the years due to allegedly heavy-handed and dirty business tactics”.

For his part, the US intelligence described McKenzie as a “consummate promoter” who had his fingers “in a wide assortment of desks in which many government topsiders cooperated and from which they profited… these deals more than anything else have kept the Moi/Njonjo group together”.

The death of McKenzie was an indicator of how deadly the region was in terms of business, wheeler-dealing and regional trade.

The players in this game were at the top echelons of government and touched on geopolitics.

But whether the “white Rat” was involved, and why, has never been known.

Mystery behind Bruce McKenzie’s death lingers on

Nation Media Group

June 01, 2019

Just before the second Lancaster Conference on Kenya’s independence in February 1962, Tom Mboya, (Justice and Constitutional Affairs minister), Bruce McKenzie (later Agriculture minister) and James Gichuru (later Finance minister) went to West Germany.

Many western countries wanted to woo perceived moderate Kenyan leaders.

However, according to confidential papers recently released in London, the visit ended on a scandalous note when the Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs found out that McKenzie was trying to recruit German striptease girls for his nightclub in Nairobi. The Germans mentioned the issue to the British ambassador in Bonn.

McKenzie was a man of mystery — even now, 41 years after his death. His secretive nature made him an excellent wheeler-dealer and foreign spy agent.

As a white man, he was not considered a threat to Kenya’s divisive politics.

Owing to Kenya’s diplomatic weakness in those early years, he was instrumental in promoting ties between Kenya and European nations.

FICKLE

However, intelligence documents paint him as a double-crosser.

In 1968, when Britain and Israel were engaged in rivalry over Kenya’s security contracts, he secretly invited the Israelis to help train the General Service Unit, before turning around to warn the British Commonwealth Secretary that the Jewish country was doing everything possible to penetrate Kenya’s military and should be stopped.

At times, though claiming to pursue Kenya’s interests, he exercised his influence for his gain.

At the time of his death, he was a director of more than 20 Kenyan firms and had business interests in Canada, Saudi Arabia, the US and Brazil.

Playing a pivotal role in McKenzie’s business success were his opportunistic tendencies.

He was among the first Europeans who read the wind of change and sided with African nationalists.

At first he befriended Mboya, then shifted his allegiance to the “Gatundu group”.

MURDER

He got into an unholy business relationship with Daniel arap Moi, Charles Njonjo and President Idi Amin of Uganda.

Moi had established business links with Amin just after the despot took power, and the two were friends until 1974 when McKenzie’s intermediary role became more important.

When one balances as many interests as McKenzie did, one makes money, friends and enemies.

Although the popular lore was that he was killed by Amin, a confidential report compiled by the East African Research Department of Foreign and Commonwealth Office said it was the work of the Criminal Investigations Department on behalf of influential people in Kenya.

A powerful minister from central Kenya who served under Kenyatta and Moi appears in the report as a main culprit.

A day before he flew to Uganda, McKenzie, at a dinner organised for the representatives of British firm Vickers Ltd, confided in those present that he was meeting Amin the following day to discuss the resumption of regular flights between Entebbe and Nairobi.

KAMPALA TRIP

He also promised Vickers that he would raise with Amin to settle a debt owed to the company on work done at Tororo Cement factory. But he also had his personal deals to seal.

Accompanying him was his close business associate and Wilken Avionics Managing Director Keith Savage and Gavin Whitelaw, a former senior accountant with Lonrho.

Whitelaw’s presence on the doomed flight was also a mystery.

The night before the trip, McKenzie had told John Watts of the British High Commission that he would be landing in Kenya from Britain though he didn’t know the day of his arrival.

It is also possible that he was lying since it later emerged the three were trying to arrange a major arms deal with Amin.

In Entebbe, the three spent most of the morning of May 24, 1978 in a meeting with Amin.

Seven to eight minutes flying time to Nairobi, the piper Aztec 23 crashed in Ngong killing all on board. Investigations suggested a bomb explosion.

INVESTIGATIONS

Kenya consequently sent a telegram to Uganda demanding answers. Uganda said the aircraft had been under guard.

Despite Kenya’s strong protest, Njonjo sent a private message to Amin saying he did not believe Uganda was involved.

On June 2, 1978, samples were sent to Britain Royal Armament Research & Development Establishment (RARDE), London.

A secret report isolates three possibilities about the concealment of the bomb.

First, the device might have been hidden among personal hand luggage “which had been found on the seat by a person who had gained access to the cabin”.

Second, the bomb could have been “hidden in a jacket on the seat and was concealed by a second jacket”.

Finally, that the device was “introduced into the personal hand luggage of the victims and unwittingly taken aboard by him”.

The report added that the nitro-glycerine-based device was likely to have been a commercial blasting explosive.

“The damage to the aircraft and the injuries to the victims are consistent with the involvement of about 21b of an explosive of this type,” the report said.

COVER-UP

RARDE refused to hand over the report to Kenya unless £4,334 (Ksh555,000) was paid.

RARDE still insisted it would only dispatch the report upon receiving a letter from Kenya authorising payment, which was consequently written by CID director Ignatius Nderi on August 1, 1978.

But it seemed Kenya had made the promise simply to hoodwink the British into releasing the report, for it took another year of nagging by RARDE before payment was made in July 1979.

RARDE’s analysis was never made public. Instead, Kenyan investigators released their own version in May 1979.

The CID said McKenzie was killed by a time bomb planted in a stuffed lion’s head given to him by Amin. This theory was dismissed by the East African Research Department as a cover-up.

The stuffed lion head theory had first been perpetuated by a South African journalist called Colin Legum in an article published in the UK Observer in February 1979.

A THREAT

When officials from RARDE privately questioned him, he mentioned his source as Njonjo, Deputy Parliament Speaker Fitz De Souza and unnamed Israelis.

So, what could have influenced McKenzie’s assassination? Perhaps the answer lies in a comment made to Sir Stanley Fingland, the British High Commissioner to Kenya, two months before the crash.

“McKenzie had discharged his main and outstanding contributions to Kenya in the past and that he was becoming anachronistic and perhaps a dangerous one in the present and future Kenya.”

Fingland agreed with this, describing it as “a fair and objective judgement”.

The British spy who reigned in Jomo Kenyatta’s Cabinet

Nation Media Group

When a pre-burial service was held in London for Jomo Kenyatta’s former Cabinet minister Bruce McKenzie, a few days after his private plane exploded as it overflew Kibiko market – four kilometers from Ngong Town – one man stood out in the crowd: Last colonial governor, Sir Malcolm McDonald.

Although the government of then UK Prime Minister James Callaghan was well represented, only McDonald – more than anyone else at the ceremony – knew McKenzie’s spy network in East Africa.

Exactly 38 years ago this week, after his plane was brought down in May 1978, by Uganda’s President Idi Amin, secret letters have also emerged which indicate that indeed McKenzie was working for some other forces inside the Cabinet.

How Kenyatta fell into this ruse is not clear: But he did.

Although the James Callaghan government, in a message read by Air Marshall Sir Geoffrey Tuttle, said Bruce “had died for Kenya – the country he had done so much for” – only a few knew McKenzie’s other activities.

If they knew, they would never have uttered a word in public. (Not then).

It is a story that explains how ties with the former colonial power continued, and it informs how British companies continued to dominate both commerce and industry in the country after independence.

It also informs how they got exclusive tenders and retained a foothold locally.

The secret letters authored by McDonald to some officers in the UK now indicate that McDonald may have personally influenced the choice of McKenzie as a spy within the Cabinet and for his continued stay in Kenya despite some distrust from key officers in London.

For starters, McKenzie was a white South African and surprisingly Kenyatta had retained him from the exiting colonial government as the minister for Agriculture and Animal Husbandry. But he was more than that and was the ultimate tenderpreneur.

In a letter dated September 21, 1964, and now at the National Archives marked “Private and Personal”, MacDonald tells Duncan Sandys, the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations: “Between you and me, I am told that your new advisers about Kenya distrust Bruce McKenzie and are liable to be prejudiced against anything that he suggests.”

DISLIKED EACH OTHER

McDonald sought to explain the genesis of that mistrust as a fallout between McKenzie and a former British High Commissioner to Kenya, Geoffrey de Freitas.

Even though it is not clear why the two disliked each other, McDonald says: “Possibly it flows from a very strong dislike of Bruce which Geoffrey de Freitas developed whilst he was High Commissioner here, and which he may have allowed to colour his advice to London on policies concerning Bruce’s ministry.”

The policies in question concerned the redistribution of agriculture land in the white highlands. McKenzie was insisting on UK providing enough money to purchase the white-owned farms for redistribution to locals but Britain was for piece-meal take-over.

This explains why the willing-buyer willing-seller policy was flung onto Kenyans and why the land question is still a problem, more than 50 years later.

McDonald told Sandys that it was unfortunate that the two fell apart.

“It was most unfortunate that a mutual antipathy grew between Bruce and Geoffrey whilst the latter was here, and I do not necessarily suggest that the fault was all on Geoffrey’s side – though from my own knowledge of the beginnings of their quarrel I think he (Geoffrey) was mostly to blame.

His prejudice against Bruce was one of the several very serious misjudgements that he made in Nairobi, which caused his mission here to be in some ways … unfortunate.”

Although McDonald does not dwell much on the details of what Geoffrey de Freitas failed to do in Nairobi, he tells the Colonial Secretary: “It is easy to find fault with Bruce. I could fill a page with a catalogue of his defects, just as he could no doubt fill a page with a catalogue of mine. But he has many other qualities and is a superb servant of Kenya and of friendship between Kenya and Britain.

Indeed during the last two or three years he had done more than any other white man in this country to maintain the latter cause and he is still doing “more than anyone else.”

Besides being a government minister, McDonald does not explain what “more work” McKenzie was doing “more than anyone else” for Britain.

What we now know is that McKenzie, after he was appointed to the Kenyatta Cabinet, started to earn respect from several British people who knew what he was up to and some said as much. He was also helping British firms get lucrative tenders inside the Kenyatta government.

For instance, McDonald told Sandys in a telling note: “A lot of individuals who used to criticise him now admit that fact, and they have become his staunch admirers in spite of the difficult abruptness in his manner which sometimes makes him unnecessary enemies. The more we can back him in his policies, the better things will be between Britain and Kenya.”

And as a final world, McDonald told Sandys on McKenzie: “Another of his achievements, he has Kenyatta’s and most other ministers’ firm trust and friendship.”

Interestingly the letter, which was meant for Sandys, was also copied to the Duke of Devonshire, the man who had officially complained that McKenzie had talked of discreet matters concerning who would become Kenyatta’s bodyguard “to all sorts of people” in London.

A former ally of McKenzie once told me that the Cabinet minister was a “loud mouth”.

Because of his local networks, McKenzie managed to be appointed director of various blue-chip companies and was in several parastatals. His word on the locals suitable to join the boardrooms of British companies was treated as final. No wonder McKenzie became one of the richest Kenyans with his firm DCK Kenya Ltd owning huge tracts of land in the Rift Valley and shares in several companies.

He was also the chairman of Cooper Motors Corporation (CMC) and is the man who brought in former Attorney-General Charles Njonjo into the league of billionaires.

BECAME KEY CONTACT

It was these activities – especially the supply of Land Rovers and security systems to the government – that saw him become a key contact of British Empire in East Africa. Some sources claim that he also worked for Israeli companies which were interested in setting up base in Kenya. It also led to his demise.

McKenzie doubled as the East African agent for a giant British electronics firm, based in London, dealing in military and police telecommunications and when he died, he was accompanied by Keith Savage, a leading Freemason and the managing director of Wilken Communications.

But if he had mastered the counter intelligence, he met his match in Uganda’s dictator Idi Amin, a man he ironically helped to get international recognition.

On March 3, 1971, it was McKenzie who urged Britain to supply Amin with security equipment quickly, saying the new Ugandan president was relying primarily on Israel.

He also flew to Israel to see Prime Minister Golda Meir and General Moshe Dayan on behalf of Amin. Despite that help, and seven years later, Amin had McKenzie killed, by placing a bomb on his plane as he left Uganda after a brief visit. The visit was ironically planned to try and have Amin purchase some weapons and security equipment.

McKenzie lived dangerous in the world of espionage.

There is still the unresolved case of August 23, 1965, when a man crawled into McKenzie’s Cottage at Diani Beach. Although police said that he attempted to take off with the minister’s keys, McKenzie, who always carried a loaded pistol, quickly noticed the intruder and shot him dead.

Even before the police started investigations, McKenzie called his Cabinet colleague Charles Njonjo and informed him about the incident. Njonjo quickly drafted a statement: “I wish it to be known in case there should be any rumour to the contrary that this incident will be investigated by the police in the same way as any other similar occurrence and the result of the police inquiry will be submitted to me in accordance with the law.”

The man was identified as Mkungu Hassan. One question which has never been answered was who had sent Mkungu Hassan. And it is not clear why he would crawl to McKenzie’s cabin to just steal some keys.

Interestingly, the report of the inquest was not made public and McKenzie was absolved. Later attempts by Central Nyanza senator DO Makasembo to have the matter discussed by the Senate were frustrated by Speaker Muinga Chokwe.

“This is a very serious matter because when a European kills an African it is taken lightly but when an African kills a European the government takes the matter seriously,” Makasembo told the Senate before the Speaker cut him short.

Makasembo’s motion read: That in view of the apparent public disaffection with the result of the inquest and subsequent court ruling in connection with the shooting and killing of Mkungu Hassan this Senate calls upon the government to institute immediately an Independent Commission of inquiry into the case”.

A similar attempt by then Rendille Representative, ED Godana, at the House was thwarted by Humphrey Slade.

If they had succeeded, they would have blown the cover of the activities of Bruce McKenzie and the reasons why he got away with murder.

Some 38 years after his death, McKenzie’s policies still inform Kenya’s relations with Britain and Israel. It was a network that he built for several years. But only snippets of his work continue to crop up, now and then.