The death of Jonas Savimbi and the end of Angola’s civil war

15 February 2003

By Sunni M. Khalid

For the better part of 40 years, Angolan rebel leader Jonas Malheiro Savimbi was the unquestioned and brutal leader of one of Africa’s most successful and destructive guerrilla movements. He had personally cheated death countless times. This longevity was an astonishing achievement given that he survived the best efforts of Portuguese colonial forces in the 60s (including the dreaded secret police of that era, International Police for the Defense of the State or PIDE), tens of thousands of Soviet-backed Cuban expeditionary forces in the 70s and 80s, and the rival Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) — which has governed the oil-rich southern African country since the Portuguese left in 1975.

For much of his public life, Savimbi had been lionized by many Western political conservatives and Evangelical Christian leaders as a “democrat” and freedom fighter” for battling against Communist-backed forces during the Cold War. President Ronald Reagan, who hosted Savimbi at the White House in the mid-80s, compared the rebel to Abraham Lincoln. Long ignored were persistent and credible allegations directly implicating the rebel leader in severe human rights abuses within his National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) movement. In subsequent years, Savimbi stubbornly refused to disappear from the international spotlight even after the Cold War ended.

While many regional conflicts around the globe were resolved through diplomatic means, led to elections, political power-sharing agreements and treaties, Angola’s bloody civil war burned on, fueled as much by Savimbi’s personal will as much as billions of dollars in sales for oil and diamonds. While other former rebel leaders had accepted new roles, leading the loyal opposition in parliaments, becoming cabinet ministers, or had gone into comfy retirement or exile abroad, Savimbi had soldiered on.

Even though he had spent many years moving through the corridors of power in civilian clothes, the UNITA leader never seamed at ease, his large brown eyes always scanning the room or darting, as if he were always looking for the exit. So, Savimbi chose to remain with his feet planted firmly on Angola’s blood red soil, ceaselessly moving through its thick forests, criss-crossing the valleys, trampling through elephant grass in the savannas, carrying on what had always been a very personal war – no matter what well-meaning foreigners wanted to believe. Savimbi worked mostly in the shadows that fell in the countryside outside Angola’s cities.

Yet, by November 2001, Savimbi’s world finally appeared to be closing in around him. Government forces had delivered a series of military blows against his highly-disciplined Kwachas, driving both Savimbi and his followers from their redoubt in the densely-forested Central Highlands. The rebel leader and his closest followers were forced out of their native Bie province, pressured steadily eastward by the Armed Forces of Angola (FAA) into the open, rolling savannahs of neighboring Moxico province.

Savimbi was having a difficult time trying to keep up with the new global situation.

A new international regime on conflict diamonds, or blood diamonds, had drastically reduced UNITA profits, estimated by many sources at several million dollars annually, from smuggling gems it mined in the northern part of Angola. United Nations diplomatic sanctions had closed UNITA’s overseas missions, making travel and communications problematic. And longtime allies, like Mobutu Sese Seko in what had been Zaire, had been driven from power, or died, cutting off logistical lifelines and rear bases that had helped sustain UNITA in the past. (The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had once used the long runways at an air base in Kamina to airlift supplies to UNITA).

n Washington, Texas Governor George W. Bush had finally prevailed in the most highly-contested presidential election in U.S. history. Even more encouraging, some of Savimbi’s old right-wing, Cold War supporters, like key Bush political strategist, Karl Rove, would be moving back into positions of power. During the 80s, Savimbi had easily charmed Washington’s neo-con elite at cocktail parties, giving his strident anti-Communist gospel incongruously dressed in a dark, collar-less Mao jacket.

Never the capitalist or Third World democrat his fawning admirers portrayed him to be, Savimbi was the consummate guerrilla; telling his sponsors whatever they wanted to hear. He had parlayed that into a quarter-billion dollars worth of covert arms from 1985 to 1992 from the CIA during the last years of the Cold War. But any hopes of rekindling this relationship were remote, given Savimbi’s own record of perfidy, and the fall of the Berlin Wall. The Clinton administration had finally extended diplomatic relations with the MPLA government in 1993, which the U.S. had withheld for nearly 20 years. Angolan military leaders, not UNITA generals, were now paying regular visits to the Pentagon. And increasingly strong diplomatic ties developed between Washington and Luanda – lubricated by the exploitation of Angolan oil reserves.

Savimbi had seen and survived desperate times in the past, but never had the tunnel towards achieving his lifelong political ambition — one day becoming Angola’s president – seemed so long and so dim. To those who had known him for years, outwardly Savimbi’s drive and determination remained as strong as ever, despite the setbacks.

The bearded, barrel-chested Savimbi’s large, whose large brown eyes always seemed to bulge from their sockets, appeared alert as ever in the field. He remained a superb battlefield tactician, resourceful and wise. Still a charismatic, if not dashing figure, Savimbi seemed forever clad in combat fatigues, a felt beret with four gold stars atop his head, a swagger stick in one hand and his trademark pearl-handled revolver ever-present at his hip. Photos of Savimbi taken over the years suggested that Africa’s oldest living rebel had defied the aging process. It was hard to believe he was 67-years-old, a senior citizen still calling the shots in what was essentially a young man’s game.

But some of his loyal longtime followers, many of whom had been raised in the Stalinist-run movement, secretly began to have their doubts about the resolve, if not the resiliency, of the man they had been taught to refer to reverentially as “Mais Velho” (“Most Eldest”).

There were subtle clues over the years, which came in the form of more frequent outbursts of anger, where he would severely punish an aide over a seemingly trivial transgression. There were also rumors that Savimbi, who had battled alcoholism in his younger years, had once more picked up the bottle. Yet, he never appeared to be slipping into a bout of depression or self-doubt. But even this had changed suddenly.

At a conference of the UNITA’s military commanders held that August 2001, deep in the bush of the Central Highlands, Savimbi seemed uncharacteristically morose, and even distracted. He’d used the occasion to take stock of UNITA, the party he founded in 1966. Savimbi took the opportunity, for once, to tell his lieutenants that he’d made mistakes in the past. This was not a dramatic admission of defeat, a concession that his quest was over. But it was an indirect admission of personal failure, something totally unexpected from a man many considered to be a megalomaniac.

Savimbi declined to enumerate any specific mistakes, but there were many from which to choose. These included his ill-fated decision to reject the results of the 1992 national elections (universally judged by the international community as free and fair) and renew Angola’s long civil war. Savimbi’s ill-conceived, one-man election campaign had been a disaster, amounting to a three month-long harangue, in which he insulted and threatened nearly every possible ethnic and political constituency. Still, his enormous ego could not withstand the “humiliation” of a close second-place finish, or the prospect of another defeat in a presidential run-off that he had earned. It was a decision that cost him the lives of some of his highest-ranking lieutenants and followers in a shoot-out with government forces in the streets of the capital, Luanda, including UNITA Vice-President Jeremias Chitunda, and his trusted and ever-bellicose nephew, Elias Salupeto Pena.

Savimbi also did not mention that he’d reneged – twice – on agreements he’d made with the United Nations. Instead, he perpetrated an elaborate hoax of disarming his guerrilla army and entering into a power-sharing agreement with the ruling MPLA. Then, of course, there were the ceaseless bloody internal purges, in which Savimbi had systematically liquidated many of UNITA’s best and brightest, along with their spouses and children, for fear that they might challenge his absolute authority. In scenes reminiscent of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge, some of the accused had even been forced to walk into public bonfires at gunpoint – after being publicly declared by the UNITA leader as “witches.” All but Savimbi were considered expendable, but as a movement, UNITA was eating its seed corn.

Of course, self-criticism was part of the revolutionary ethos in a Marxist-Leninist movement, which UNITA had always been. But it was Savimbi alone who exercised life-and-death control over everyone in UNITA. He had been beyond criticism from even the most senior officials, who both feared and loved him. But now, “Mais Velho” was taking at least some of the blame. While he continued to preach UNITA’s higher goals of self-discipline and self-sufficiency, and in fact, reiterated his firm belief that the movement would eventually rule Angola, for the first time Savimbi told his most obedient followers that he might not live to see it. A high-ranking UNITA diplomat in the West, said those who attended the meeting “were shocked at his tone. He was really delivering an apology to the movement.”

Savimbi had come full circle, transforming himself from armed rebel to politician, before reverting back once more to an armed rebel. Unlike his nationalist guerrilla contemporaries — like Namibia’s Sam Nujoma, or what Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe used to be — Savimbi had not become a popularly-elected head-of-state or a national hero. Nor would Savimbi become a revered elder statesman, like Nelson Mandela in South Africa. But he had little to show for a lifetime of struggle. In fact, wandering in Angola’s vast countryside, he was further away from taking power in Luanda than he’d been at the start.

Now, Savimbi and most of his closest remaining confidantes, and their families, making up two columns, were on the run, being pursued doggedly by elite units of the Angolan Armed Forces, or FAA, some of which were being led by former UNITA commanders. The UNITA leader used his satellite phone sparingly – sometimes as infrequent as once a week — for fear of giving away his exact position to the pursuers at his heels.

When Savimbi did talk by phone, he was instructing his diplomats in the West to do whatever they could to re-start peace talks with the government through the United Nations. The U.N. was, justifiably, sanguine about UNITA’s true intentions – they had been manipulated and lied to by Savimbi in the past. Savimbi made feelers to the Saint Egidio in Rome, hoping the Roman Catholic priests might intervene and offer to mediate as they had in resolving Mozambique’s civil war a decade before. But that was a long shot. Besides, the MPLA government, led by Savimbi’s longtime nemesis, President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, was even more reluctant, now that they were on a roll militarily and once again had the rebel leader in their sights. The time for any serious negotiations with a Savimbi-led movement, or any talks at all, had passed.

In the midst of this grim situation, Savimbi made an unusual personal request to his some of his remaining diplomats in the West. In the past, the UNITA leader had usually requested that they send him books or music. His literary tastes were eclectic, ranging from philosophy, biography and history to art. But his musical tastes usually favored classical composers, specifically Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart – an odd cultural phenomenon among the educated elite in many Central African capitals. The rebel leader disdained most of Angola’s lively, Latin-tinged popular music (most artists supported the government and had personally targeted Savimbi in some of their songs). Savimbi, however, had also been a fan of the music of late Jamaican reggae superstar, Bob Marley.

But this time, he wanted just one particular song on a CD produced by one of Marley’s contemporaries, crooner Jimmy Cliff. The title of the song Savimbi wanted? “Many Rivers To Cross,” a lilting, melancholy ballad first performed by Cliff in the mid 1970s.

The request was dutifully taken down by one of Savimbi’s senior diplomats in the West, without any consideration of it poignancy. “Mais Velho” was never to be questioned or second-guessed by anybody within the movement, no matter how seemingly trivial the issue. And none of the UNITA sources interviewed for this story know if Savimbi’s clandestine request – his last — was fulfilled before his death three months later.

But for anyone familiar with the lyrics or melody of the song, or the guerrilla leader’s plight at the time, it becomes easily apparent why Savimbi had requested this particular piece of music. Over the decades, the UNITA leader had waded through and crossed Angola’s many rivers innumerable times. In fact, in recent years, Savimbi is said to have traveled most often by a motorized, dug-out canoe, from clandestine river base to clandestine river base. The words may well have represented not only the literal, but the metaphorical as well, reflecting the UNITA founder’s increasingly somber mood. As events unfolded, Cliff’s lyrics could just as easily been writing the final chapter of Savimbi’s life, or even delivering his eulogy.

Even if the Cliff CD had been delivered to Savimbi, it seems unlikely that the UNITA leader would have had much leisure time to listen to it. He was pre-occupied with not only trying to hold his crumbling guerrilla army together, but also with ensuring his own daily survival. No longer several steps behind, government forces were eagerly nipping at Savimbi’s heels. Desperation became his constant companion.

A few weeks later, in early December 2001, all satellite telephone communication from Savimbi’s column moving eastward in Moxico province ceased. At the same time, government communiqués regarding the hunt for Savimbi painted a grim picture of a cornered, increasingly desperate commander, whose forces were deserting amid starvation on one hand, and more heavily-armed and more numerous government troops on the other. In many ways, Savimbi began to re-live the last days of the life of one of his personal heroes, Che Guevara, the Argentine hero of Cuba’s revolution, who was tracked down in a similar way in Bolivia in 1967.

The size of Savimbi’s column was large, by some estimates, numbering close to 400 people. But it was far from a fighting force. The number of actual soldiers was estimated at less than half that total; the rest were women and young children, specifically the families of the UNITA fighters. This unwieldy group could neither move far, or fast. And whenever Savimbi personally moved about, a thick cordon of bodyguards physically surrounded him. This was aimed at leaving any presumed FAA snipers, or would-be assassins within the column, with no clear shot at Savimbi.

The government issued a series of news bulletins, stating that their forces were close to the ever-elusive Savimbi, or had cornered the UNITA leader. Savimbi, of course, had proven over the decades to be a master of escaping dozens of attempts by the Portuguese, the Cubans and the MPLA to kill or capture him. Certainly, previous rumors of his demise had been disproved.

Yet, this time, the noose finally seemed to be tightening inevitably around Savimbi’s husky neck. The superior firepower of reorganized government troops, first under FAA chief-of-staff General Joao de Matos, had destroyed UNITA’s conventional forces in previous engagements and had driven Savimbi from his headquarters in Huambo in 1994. It was the equivalent of a boxer landing a hard punch right before the bell ending a round – effectively discombobulating the opponent, without giving them an opportunity to recover or respond. The defeat was so stunning that it forced UNITA to agree to the Lusaka Accords, where Savimbi once more pledged to disarm his forces and re-join the political process.

Savimbi did not attend the signing of the 1994 agreement, citing concerns, as always, over security. He turned down an offer from the U.N. to have its top military commanders accompany him on the flight to and from the Zambian capital. Instead, he deputized top UNITA leader, General Eugenio Ngolo Manuvakola, for the ceremony. However, when Manuvakola returned to Bailundo, Savimbi publicly denounced his former trusted lieutenant for betraying UNITA and signing the agreement — precisely what Savimbi had instructed him to do. Manuvakola was immediately imprisoned, but managed to escape with his family some three years later. After his escape, he showed up in Luanda, not to defect to the government, but to lead a dissident wing of Savimbi’s party, known as UNITA-Renovada.

Manuvakola had company. Several UNITA leaders, who had been trapped in Luanda when the civil war resumed in 1992, formally joined the National Assembly five years later. They took the 70 seats UNITA had won in the parliamentary elections, were appointed to ministries, and became part of the loyal opposition to the ruling MPLA.

Protected from Savimbi’s wrath for the first time, many of his former comrades were easily co-opted by the government. Some publicly parted company with Savimbi and joined UNITA-Renovada, although there were continuing ongoing struggles for leadership of the splinter party.

Longtime Savimbi crony, Jorge Valentim, became Angola’s Minister of Tourism, a post that gave him a steady salary, a large house and luxury cars. Valentim quickly became a prominent fixture in Luanda’s social scene. He was not alone as a pampered member of the government’s own “loyal opposition.”

Only Savimbi’s nephew, Chivukuvuku, remained politically loyal to his uncle. But even he had no desire to return to the bush at his side. He certainly had the opportunity to do so. The MPLA, no doubt, kept an eye on him in Luanda. Chivukuvuku traveled unescorted at least twice to Europe for further medical treatment for the wounds he received to both legs in the fall of 1992. He could have easily flown to Zambia and melted across the border to re-join Savimbi. But he did not. The handsome former UNITA foreign minister and Western media darling remained in his seat in the National Assembly in Luanda. Perhaps he feared suffering a similar fate to that of Manuvakola, or even Pedro “Tito” Chingungi, Wilson dos Santos, Jorge Sangumba and dozens of former high-ranking UNITA members who died at Savimbi’s hands.

As with the previous agreement, Savimbi cheated on the Lusaka Accord. Instead of sending in his best troops to demobilization sites, he sent old men and young boys, while holding his best units in reserve in the bush. The UNITA used the two-year respite to rebuild its forces.

When the war resumed in earnest later in 1996, UNITA had managed to organize mechanized units, including tanks and armored cars. But the rebels did not have an air force. The FAA gradually decimated UNITA’s conventional military might and Savimbi’s forces reverted to the classic guerrilla tactics employed in the movement’s earlier years.

Savimbi returned to his ethnic redoubt in his native Bie province. But it was no longer secure. During Angola’s rainy season in late 1998, between November and December, the government forces launched a major offensive aimed at capturing Savimbi’s stronghold in the villages of Bailundo and Andulo, where he had been raised as a boy. Apparently tipped off beforehand, UNITA thwarted the offensive amid heavy fighting. The rebels repeated the feat the following March, again, inflicting heavy losses on the FAA. A UNITA Colonel later told Angola scholar Gerald J. Bender that the government commanders had made it easier for the rebels by using the same battle plan. “The MPLA are like elephants,” the rebel said, “they take the same path to the water every night.”

But these defeats did little to discourage the government, which was still determined to flush Savimbi from his Bie stronghold.

In November 1999, the government forces finally drove Savimbi out of his headquarters in his childhood villages of Bailundo and Andulo. Prior to the third attack, the FAA had reportedly acquired some sophisticated military equipment and was able to determine that UNITA had been monitoring their communications. This time, they falsely telegraphed their plan of attack. UNITA threw up defense around the familiar routes, but were then surprised when the FAA attacked from three different directions. The rout of the rebels was as sudden as it was shocking. Even Savimbi was forced to flee in such haste that food was left cooking on the stove. FAA troops seized many personal items, including stacks of top-secret documents, computers and floppy discs tracking UNITA’s weapons-for-diamond trade, Savimbi’s clothes and even several personal photo albums, which the government proudly displayed to the public.

The government’s air force, no longer hindered as it had been a few years before by South African forces that once flew from air bases in Namibia, or CIA-supplied Stinger missiles, was now able to strike UNITA with impunity, virtually anywhere throughout the country. The “safe harbor” that Savimbi once enjoyed in remote Jamba, located near Angola’s border with Namibia and Zambia, was a distant memory; UNITA’s sanctuaries within Angola were gone.

On the battlefield, many of UNITA’s best commanders were now fighting on behalf of the government’s forces. In fact, many of them distinguished themselves within the FAA by winning battles against their former comrades-in-arms. Their replacements within UNITA had neither the experience nor the skills of their predecessors, losing engagement after engagement. And even their ranks were thinned by Savimbi’s continuing purges.

Among the most prominent of the continuing list of victims included the exceedingly vicious, one-armed General Altino Sapalalo or “Bock,” one of Savimbi’s longtime comrades-in-arms. “Bock” was imprisoned upon Savimbi’s orders and then executed in December 1998, when “Mais Velho” held him personally responsible for another in a series of defeats to superior government forces. This underlined the fact that within UNITA, everyone was replaceable, or expendable, with the sole exception of Savimbi.

U.N. sanctions against the movement had closed down UNITA’s diplomatic offices in Washington and Western Europe. A travel ban was being enforced on UNITA diplomats, further reducing Savimbi’s communication with the outside world. “Dr. J” could still get by with a little help from some of his friends in West Africa, like Togo’s longtime dictator Gnassingbe Eyadema and his bloodthirsty protégé, Blaise Compaore, the ruler of Burkina Faso. Both men fenced diamonds for Savimbi and allowed their countries to be used as transshipment points for arms to UNITA.

South Africa’s white-ruled regime had been swept aside by the MPLA’s ally, the African National Congress, in historic all-race elections in April 1994. Venerated anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela, not F.W. De Klerk or P.W. Botha, held the reins of power in Pretoria. (Savimbi would later meet Mandela in South Africa in an unsuccessful bid to have the South African leader mediate a resolution to Angola’s civil war.) Covert supplies to UNITA were still ferried clandestinely out from South African airfields, without government knowledge, but they were insufficient.

The MPLA had also sent troops into Congo-Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Mobutu’s Zaire) to help prop up new regimes, as well as stanch porous borders.

Pressure from Luanda also slowed the flow of arms to UNITA across the border with Zambia, where aides close to President Frederick Chiluba had profited handsomely from illegal transactions with UNITA. When faced with the threat of an Angolan invasion of parts of western Zambia, Chiluba’s government belatedly cracked down on UNITA. And in northern Namibia, FAA and Namibian troops mounted joint operations against UNITA along the border. A trap was gradually closing on Savimbi.

Meanwhile, the MPLA government was growing stronger. There was nothing UNITA could do to stop the flow of Angolan oil to world markets. A million barrels-a-day from Angola’s offshore oil wells translated into more than $5 billion –a-year in oil revenues for the MPLA government. Initially, after the war resumed, the government began to mortgage years’ worth of production for hard cash to rebuild its army. Then, with discoveries of new reserves and steady increases in the world price for oil, the government was able to buy whatever weapons and training its forces needed against UNITA.

Savimbi, himself, remained largely silent. He could no longer use his satellite phone at random, for fear of giving away his position to the prying ears of government electronic eavesdroppers attempting to fix his exact position. There was abundant proof for Savimbi to fear using his favorite form of communication.

In the summer of 1994, an ingenious government assassination plot, using hand-held GPS (Global Positioning Systems) units and air strikes, missed the UNITA leader by yards, and forced him from the public sight for several months, and prompted rumors that he was seriously wounded or dead. In fact, Savimbi’s ever-present aide, “Cacique,” was killed in this assassination attempt. His duty was to carry “Mais Velho’s” satellite phone, and those within the movement said he never strayed more than 20 feet from Savimbi. If nothing else, the UNITA leader was more concerned than ever about his personal safety. While Savimbi hibernated, General Paulo Lukamba, or “Gato,” (who was married to one of Savimbi’s nieces, Violetta Pena) spoke on his behalf to the outside world, and even this was done on an infrequent basis.

On the rare occasions when Savimbi did speak publicly, it was in short interviews to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and Voice of America (VOA). But the voice heard on the other end of the line was not that of the supremely confident guerrilla commander of another era, but pathetically that of a tired, lonely, old man. Savimbi’s monologues revealed a man who had not come to terms with a new political dispensation, one that left him, and the movement he had founded, in utter isolation. In these infrequent talks, Savimbi rambled, appealing for international mediation and another round of negotiations with the government.

My friend, Portuguese journalist Luis Costa-Ribas, then working for VOA, and I spent several weeks in the fall of 1994 trying to track down an almost unbelievable story of a “Golda,” a Jewish doctor, who held U.S., Israeli and South African citizenship. He was trying to arrange for Savimbi and his closest aides to go into political exile as part of a deal to end the civil war.

In fact, “Golda” was trying to arrange a considerable fee of several hundred thousand dollars for himself for this service, even sending out feelers to Luanda. The “good doctor” never got through to personally see Savimbi, who remained in total seclusion for several months. Ultimately, “Golda” made it to Bailundo, but never managed to negotiate face-to-face with “Mais Velho,” who refused the deal through his aides.

The Israeli connection was yet another interesting footnote to a regional conflict that had been wildly internationalized from the start. Each side worked assiduously to line up patrons in every far-flung corner of the globe.

During this time, Luis, Jerry Bender and I began to joke that maybe the MPLA should pay the Israelis themselves to track down and kill Savimbi. We were all aware of the ingenuity and daring the Israelis had displayed time and again in killing several high-ranking Palestinian guerrilla leaders, from Gaza and Beirut to Tunis. The Israelis often bragged that they knew the exact whereabouts of every Arab head-of-state on a 24-hour basis, with the possible exception of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. Few within the intelligence community doubted them.

We all thought it would be far cheaper for the MPLA to simply hire the Israelis to “whack the old man,” than spending billions of more dollars to re-arm and re-train their conventional army to chase the UNITA leader around the Plano Alto into perpetuity. Of course, for the MPLA, money was no object. And arranging massive, foreign military packages had become the time-honored way for many Angolan government officials of putting money into their pockets through kickbacks.

It was not until two years after Savimbi’s death that I learned that the MPLA had, indeed, made an arrangement with the Israelis to track down and kill Savimbi. Rumors of foreign involvement in the operation (initially linking Portugal) had surfaced almost immediately, and then died down quickly after his death. However, I was recently able to confirm the details with some of my old, high-ranking sources in Washington.

In the fall of 2000, according to my Washington sources, an Israeli businessman, who held significant concessions in Angola’s diamond trade, approached the MPLA. Israel is the largest producer of polished diamonds in the world. And Israeli businessman have extensive contacts throughout the globe, specifically in several African countries including Sierra Leone, South Africa and the Congo. Savimbi’s billion-dollar annual slice of the international diamond trade was costing money to competitors.

The unidentified Israeli said he could assist the government’s efforts to eliminate Savimbi, who was cutting in on his profit margin. At this stage of the conflict, the government had already taken back the initiative from UNITA, controlling the cities, but Savimbi’s forces continued to roam much of the Angolan countryside freely. But they had no idea where the UNITA leader was.

The unidentified Israeli had close contacts with the IDF and Mossad, Israel’s overseas intelligence gathering service. He helped arranged for a group of former IDF and Mossad officers to travel to Angola, where they arrived in late 2000. Once there, they began the laborious task of organizing military intelligence on Savimbi’s whereabouts – something the MPLA, notwithstanding it’s near successful assassination attempt in 1994 — was never able to accomplish on its own.

Israel had long been involved in southern Africa. In the late 60s, Israel and apartheid-ruled South Africa had shared military technology in the development of fighter aircraft, long-range artillery and nuclear weapons research. Israeli military advisors worked closely with the South Africans on counter-insurgency training in Namibia through the late 1980s, and also provided assistance to RENAMO (Mozambique National Resistance) rebel forces attempting to topple neighboring Mozambique’s socialist government.

The MPLA started buying Israeli military hardware in 1994, when it was rebuilding the FAA. Items included at least one reconnaissance plane, armored vehicles and light arms. UNITA, which had been receiving Israeli light arms and training through South Africa since the mid-70s, continued to buy from the Jewish state through the black market. But the MPLA could also offer the Israelis something UNITA could not – oil.

On its face, this shaped up as another expensive boondoggle for the MPLA. Over the years, Savimbi had made a mockery of the famous line former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis uttered before he fought Billy Conn – “he can run, but he can’t hide.’ Savimbi had managed to do both for decades. Besides the MPLA’s own incompetence, there were some significant factors in Savimbi’s favor. Angola’s dimensions were far larger than the 20-by-20 foot boxing ring in which the “Brown Bomber” stalked his doomed opponents. The sheer physical size of Angola – 1,246,700 square miles — makes it almost twice the size of Texas. Locating Savimbi in an area so large appeared akin to finding a needle in a haystack — in Texas. But the Israelis were undaunted and confidently set about their job with their trademark persistence, patience and attention to detail.

The first thing this Israeli team did was to systematically revamp FAA’s military intelligence gathering system. There were sightings of Savimbi all the time. He was seen one week in Soyo, a town in northern Angola along the Atlantic Ocean coast. Then, the next week, he was reportedly seen on the outskirts of Huambo in his native Bie province. The week after that, Savimbi was rumored to be in Mbanza Congo. He used his satellite phone sparingly, if at all, so the old methods of eavesdropping on his conversations yielded little. Catching a ghost was perhaps an easier proposition than busting Savimbi. But what made the job even more difficult, the Israelis discovered, was that all these different bits of information had apparently never been assembled in a coherent, time-sensitive order. This took several months to accomplish, but the Israeli team, who were now working closely with their Angola counterparts, was successful.

The next step was the interrogation of former UNITA members, some of whom were now working as officers with the FAA. These were men who had been raised in the movement and had intimate knowledge of the rebel’s training, tactics and capabilities. Many had also served personally under Savimbi and some of his remaining military commanders. They provided valuable information about Savimbi’s personal habits, his contacts throughout the country, and locations he had frequented in the past. As UNITA’s military situation grew progressively worse, the joint Israeli-Angolan team interrogated UNITA deserters and stragglers, as well as those who were captured and wounded. Information from these sessions was vetted and then fed into the revamped intelligence gathering system.

By mid-2001, the joint team was able to ascertain that Savimbi was operating mostly from his native Bie province, still a considerable geographic area with thick vegetation. Bie had already proved a tough nut to crack for the MPLA in the past, not only because of popular support for Savimbi, but the wily guerrilla leader’s intimate knowledge of the terrain. Still, consistent military pressure from the MPLA gradually pushed Savimbi and his followers eastward into neighboring Moxico.

This was part of the overall strategy plotted by FAA Chief of Staff General Joao de Matos. He wanted to drive Savimbi away from his strongest base of support Bie into Moxico, where UNITA had long operated, but was less familiar. It was not home turf. Savimbi, like most of UNITA’s top leaders, was Ovimbundu. Most of the residents of Moxico were of the rival Chokwe ethnic group. Old antagonisms between the two groups had simmered just beneath the surface for years, which Savimbi’s heavy-handed tactics with the general populace only worsened. And, in the 1992 elections, UNITA was handily-defeated by the MPLA in Moxico. It was a stunning personal rebuke to Savimbi, who assumed that his party would win the province overwhelmingly.

The topography of Moxico, rolling, open savanna, also favored the FAA, making it easier for them to spot UNITA guerrilla movements from the air. Making matters worse for Savimbi was a severe drought that struck the province. The UNITA fighters were deprived not only of foliage they needed to hide their movements, but also of the wild fruits and game they were used to subsisting on. Stealing food from local peasants was not an option, since there were few crops available and the government had forcibly relocated a large portion of the civilian population into protected towns and villages, making much of Moxico into a free-fire zone.

By the fall, the Israelis rolled out their secret weapon – a single military drone. The Israelis have long led the world in the technology of unmanned air vehicles, or UAVs. Some of that technology was shared with the U.S., which led directly to the production of the CIA’s famed Predator, now used in the global hunt for al-Qaeda leaders, including Osama bin Laden. The Israelis have used UAVs, or drones, successfully for four decades, used primarily by the Israel Defense Forces to provide aerial reconnaissance against various Arab foes. Drones were credited for Israel’s victory over Syrian forces in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in 1982, where the reconnaissance pinpointed Syrian tanks units, which were smashed by the IDF.

Now in their fourth generation, many UAVs are a fraction of the size of a manned aircraft, far more maneuverable and much quieter. Relatively unobtrusive, drones are able fly day or night at heights of more than 20,000 feet and have a range of more than 1,000 miles. The latest types of UAVs can map large areas with high-definition cameras that can see through clouds, and stay airborne for 24 hours or more. Some models now in use are about the size of the palm of a man’s hand.

The particular drone in question has been identified by sources within the intelligence community as a second-generation, Israeli-made drone, assembled in the early 1980s. It is several steps down from the models now being produced by Israel and other nations, but it proved effective in the final hunt for Savimbi.

The Israelis fitted the radio-controlled drone with a high-definition camera and sent it skyward over central Angola. Each day, for 12 hours of sunlight, the radio-controlled craft set off to fly a grid pattern over a 200-square mile radius, mapping the general area where Savimbi’s column was believed to be. The drone was not equipped with infra-red cameras, but it took only a few weeks for it to home in on Savimbi’s party. After that, it was just a matter of time.

According to my sources, by the end of 2001, the drone was able to locate Savimbi’s position within hours of getting aloft. Although the drone flew in 12-hour daylight shifts, Savimbi’s column, now weighed down with wives and children, could not move very fast nor very far. In fact, the column could not move at all during the night. With reliable real-time information, the joint Israeli-Angola team was able to relay coordinates and other information on secured frequencies to FAA units in the field in Bie and Moxico, who were pursuing Savimbi. It is unknown whether or not Savimbi’s team knew they were being tracked by this latest high-tech gadgetry, but they must have suspected something was amiss when they could not shake their dogged pursuers.

The final weeks of the hunt for Savimbi could be compared to a team of cowboys, riding herd, controlling the movement of the cattle from the periphery, driving them into a corral and then subsequently to the slaughterhouse.

By early 2001, government forces under the command of General Armando Da Cruz continued to press UNITA inexorably to within about 100 miles of the Zambian border. Savimbi’s remaining forces were still capable of isolated ambushes, but little else.

Over the months, the ranks of the captured and UNITA defectors grew closer to Savimbi’s inner circle, including his personal physicians, cooks and bodyguards. Those who could not make it across the border to Zambia or the Democratic Republic of the Congo surrendered to government forces.

Such large-scale defections, some including more than 100 rebels, were almost unheard of in UNITA. The Kwachas were renowned for their discipline, which was brutally enforced by commanders who would summarily execute any rebel that disobeyed a command in the field or attempted to flee in battle. But now, discipline within the ranks of the battle-hardened rebels was breaking down. Their fear of death and starvation was now greater than their fear of Savimbi. Many of them, appearing bedraggled and painfully thin, spoke of appalling conditions and poor morale within their ranks. Some claimed that many of the rebels were reduced to eating tree bark. In January 2002, a captured Savimbi cook told government radio that many within the rebel leader’s column had only grasshoppers to eat and were literally starving to death.

Government officials became more confident about the fate of the war. They were close to claiming a military victory, but they could not do so as long as Savimbi remained at-large. As long as the UNITA leader was alive, he would simply will the war to continue. Meanwhile, the Israeli drone continued its mission, drawing ever closer to its quarry.

In the weeks before his death, there were serious indications that time was running out on Savimbi. For the first time, harried UNITA generals were forced to leave behind their wives and children as they fled in panic eastward to escape the relentless FAA (They had been forced to travel with their families because UNITA no longer had permanent bases). One of those who captured by the government was Violetta Pena, Savimbi’s niece and the wife of General “Gato.” She made an impassioned plea over the government-run radio for her husband to surrender. “Gato” ignored his wife’s appeal. UNITA’s desperate flight eastward essentially became a death march.

On January 15th, 2002, Savimbi used his satellite telephone to send out a short, urgent message to his diplomats overseas. It was the first time they had heard from him in more than a month. The rebel leader assured them he was safe, but also told them to re-double their efforts to re-start talks with the U.N. At this point, UNITA’s diplomats had only succeeded in having informal talks about talks, but Savimbi wanted these contacts intensified. It would be the last directive he would send out.

Six days later, the FAA came agonizingly close to capturing Savimbi. Once again, the rebel leader used one of his nine lives, perhaps his last, eluding his pursuers. The government troops managed to seize more of Savimbi’s personal items, including a transistor radio, his own special military insignia, and a rifle, engraved and given to him several years before by former South African president P.W. Botha.

The only question was if Savimbi and his beleaguered column could make it through the killing zone of Moxico to the safety of the Zambian border, before the FAA could finish them off. The answer came nearly a month later.

Finally, FAA units spotted two UNITA columns in Moxico. The rebel attempts to elude the government forces were unsuccessful. The drone flying overhead was able to distinguish which of the columns Savimbi was leading. While FAA continued to draw closer to Savimbi’s column — one source says within 500 yards — the rebels reportedly gave them a fateful break. The lead column turned on its satellite phone for the final time, making calls to France and Portugal. These calls allowed the government to finally fix Savimbi’s position.

Government forces continued to track Savimbi on the ground, knowing they had drawn closer because of the tracks made by Savimbi’s custom-made combat boots, which been stamped with a distinctive tread. In fact, sources say that Savimbi, in order to disguise his own movements, had his boots made with the soles facing backwards.

On the morning of Friday, February 22nd, 2002, the MPLA, and the law of averages, finally caught up with Jonas Savimbi. Fittingly, on a riverbank near the Angolan town of Lucesse, in the eastern province of Moxico, government forces ambushed a column led by the UNITA leader.

On the banks of the Lavuei River near Lucesse, the government sighted Savimbi, surrounded his party and then sprung its ambush.

Reportedly caught by surprise by government troops as he sat down for breakfast, Savimbi managed to reach for his pistol. He was cut down in a withering cross-fire, killed by as many as 15 bullets, including at least two shots to the head.

“Savimbi decided to rest,” said Brigadier-General Simao Carlitos Wala told government radio. “Confident, as always, he had nonetheless placed his units on alert. He fought back with gunfire, and that’s why he was killed.”

“We nailed him seven times,” added Wala, who commanded the troops who killed Savimbi. “He tried to resist with his gun, but then he was dead.”

Wala told state radio that the UNITA leader’s battle plan had failed because he had lost radio communication, following an army offensive dubbed “Kissonde,” named after an aggressive ant.

“He only had a small ground to air radio,” Wala said. “This factor blocked any chance Savimbi had to get some security from parallel units, which would have allowed him to cross a stretch of the river up at the border.”

As he vowed many times before, Savimbi died with a gun in his hand amid a hail of gunfire – about 30 miles away from the village where he had founded UNITA 36 years earlier. Twenty-one of Savimbi’s bodyguards were also killed.

The identity of the FAA soldier, or soldiers, who killed Savimbi, remains a secret in Angola. One reason cited by diplomats is the fear of retribution by some of Savimbi’s still fanatic followers. Sources close to the government say the soldiers in question have been rewarded handsomely with money and scholarships to study overseas, but this information could not be confirmed.

In the wee hours of the morning, a high-priority cable from the U.S. Embassy in Luanda reached Foggy Bottom stating tersely that Savimbi had been captured by the FAA — startling news, despite the steady reversal in UNITA military fortunes. Then, a few hours later, these reports were updated to indicate that the rebel leader had been killed. Media reports about Savimbi’s fate were consistent from the beginning.

A senior member of Washington’s intelligence community, who had helped set-up the CIA’s initial covert military pipeline to Savimbi in the mid-1970s, said there was never any doubt about the government’s intentions towards Savimbi.

“The Angolan government was going to kill Savimbi, not capture him,” said the well-placed source. “If they had captured him, it would have presented them with another problem of what do to with him. They weren’t going to take that chance.”

When news of Savimbi’s death broke over the wire services, television, radio and the Internet, many did not believe it. The UNITA leader had become a legend by cheating death so many times before that, even his enemies, believed he might be indestructible. His death had been prematurely announced more than a dozen times before. The world waited for irrefutable proof that, indeed, “Mais Velho” was dead.

The next day, the first visual images of Savimbi’s well-fed corpse (even more remarkable in that it was in stark contrast to the emaciated bodies of his followers that survived him, as well as numerous stories of famine-like conditions within that UNITA column) were transmitted electronically around the globe. A few pesky flies crawled over the UNITA leader’s face, with its familiar features – the broad nose, full beard and mustache — bearing no expression. Laid out on a table under a tree, the government soldiers carefully handled Savimbi’s stiff body; his left arm was upraised, as if he were giving a final command.

“Mais Velho’s” eyes were partially opened, a bullet had grazed his forehead, ripping away some of the flesh, just over his left eye. There was a small entry wound on the right side of his neck, another one in the back of his head. Dried blood stained the front of Savimbi’s dusty, olive-green uniform. His trousers were partially pulled down, revealing a pair of green-and-white striped bikini underwear. The UNITA founder’s boots were missing, which sparked some speculation that he may have been captured and then executed.

[Captured soldiers are usually disarmed and forced to remove their boots, to make it more difficult for them to run away.] Perhaps they were destined to be a war trophy in the office of some top government official or high-ranking soldier.

The government forces had been in hot pursuit of Savimbi for several weeks, after having driven UNITA out of its Ovimbundu ethnic stronghold in neighboring Bie province into the open savannahs of eastern Moxico. There, FAA chief-of-staff, General Armando Da Cruz, had turned the province into a vast free-fire zone, forcibly evacuating thousands of residents of the rural areas into government-controlled cities, towns and protected villages. Savimbi and his men would have difficulty trying to melt away into the open countryside, whose topography lacked a dense canopy of trees, and made it far easier for them to be observed and detected from the skies.

News of the UNITA leader’s death came on the eve of a visit by President Dos Santos to Washington, where he held talks four days later at the White House with President George W. Bush. Ironically, the first foreign policy act of the elder Bush when he became president in January 1989 had been to pledge continued U.S. covert assistance to UNITA.

But when the photos of Savimbi’s body finally reached Luanda, the residents celebrated wildly, dancing in the streets.

In Washington, one of Savimbi’s senior diplomats heard the news on television, but didn’t believe it. The next morning, he sat down and watched the video of Savimbi’s corpse. He sadly accepted the irrefutable proof that Savimbi’s very personal war was over. But he also expressed surprise.

“There was peace in his face,” said the diplomat. “Usually, when somebody dies in circumstances like that, their faces are distorted. You usually see an expression of shock, or pain. But [Savimbi] looked as if he were asleep, like he was in a deep slumber. To me, it was proof that he was ready for the moment. He basically knew the end was near. He knew his time was coming to an end. He had a feeling that his mission was accomplished.”

Savimbi’s last remaining lieutenants, General “Gato,” and UNITA Vice President Antonio Sebastiao Dembo, somehow managed to escape the ambush near Lucesse. Dembo, the only non-Ovimbundu within UNITA’s top leadership, was later reported to have died a week later in mysterious circumstances; with one version alleging that he died from starvation, a second purporting that he died from malaria, and a third alleging that he was killed by “Gato.”

The government declared an immediate ceasefire, instructing its commanders in the field not to fire on UNITA remnants. Within three weeks, General “Gato” and what was left of UNITA’s military leadership agreed to talks with the government on formally ending hostilities.

UNITA’s unofficial representatives in Lisbon and Washington were left completely off-guard. Still stunned by Savimbi’s sudden death, they did not know who had succeeded him. They were reluctant to give up the armed struggle, even though they lived comfortable thousands of miles away from the battlefields of Moxico. Even worse, they had no way to contact their leaders in the bush.

Less than a month later, talks between FAA and UNITA commanders were held in-camera in Luena. The government was represented by a former UNITA commander, General Geraldo Sachipengo Nunda; the rebels by “Gato” and General Abreu Muengo Ucuatchitembo, also known as “Kamorteiro.” (Nunda joined the FAA in 1992, when the UNITA and MPLA forces were being combined before the elections. He had chosen to remain in the government army after Savimbi pulled out most of his generals in the aftermath of the balloting. The former UNITA general was subsequently promoted to the FAA’s deputy chief-of-staff. His boss, Joao de Matos later credited Nunda’s invaluable assistance in the hunt for Savimbi.) UNITA’s overseas supporters claimed that “Gato” was being held against his will and was negotiating with the government under duress.

The government gave the UNITA leader access to a phone, which he used to communicate with his nearly hysterical charges overseas. “Gato” and his gaunt UNITA colleagues were given fresh fatigues by government forces to replace their soiled and ragged uniforms. “Kamorteiro” signed the ceasefire agreement, which committed UNITA to finally disarm and demobilize its forces.

Semantics could not disguise the fact that the document amounted to little more than UNITA’s surrender.

On April 4th, 2002, just five days later, “Gato” flew to Luanda for a formal treaty signing at the National Assembly. Luis and I had long since left VOA and NPR, but we both maintained an almost unhealthy interesting in Angola. While I continued to read up on recent events and collect Angolan music, Luis had traveled a handful of times back to Angola over the years and continued to file reports for the Portuguese television channel, SIC.

British journalist Anita Coulson, whom I’d met in reporting on the elections in Angola in 1992, and I had become great friends in the interim, exchanging several family visits between London and Baltimore. She and my wife, Zeinab, became as close as sisters. Anita had remained with the BBC, but had moved over into television news side as a producer. But she had agreed to conduct a journalism training course in Angola and, as luck would have it, she was in Luanda on the very day the treaty ending the long civil war was signed.

Ever resourceful, Anita managed to catch a ride over to the National Assembly with General “Gato.” In fact, she had booked a room next door to “Gato’s” at the Hotel Tropico. A festive, almost euphoric mood had gripped Luanda, reminiscent of the way things had been just after the elections a decade previously. I kept in touch with Anita by Internet and telephone, exchanging information. Although I was no longer reporting, I was living vicariously through her. I booked her as a guest on Africa Journal, the TV show that I now helped produce at VOA.

Anita told me that, unlike 10 years ago, “Gato” moved around Luanda without several well-armed bodyguards, or even a sidearm. The government, she told me, had de-fanged UNITA militarily and could have killed him if it wanted. However, “Gato” was alive, if for no other reason than to give the government someone to sign the peace treaty with.

UNITA’s estimated 80,000 troops trudged as a defeated army to hastily organized assembly points around the country. The government was faced with the new challenge of supporting the rebels, as well as 300,000 of their dependants. But with Savimbi dead, there was genuine hope that the Kwachas would finally be disarmed and demobilized for good.

[Unfortunately, the MPLA has not earmarked a large sum of money into quartering and demobilizing the UNITA units. Although nobody expects the war to resume, some observers say that it is possible that large numbers of former combatants could become brigands or bandits, possibly recreating an Angolan version of America’s “Wild West” that could last for decades.]

Already painfully thin to begin with, “Gato” appeared emaciated. Anita told me that she had eaten breakfast and lunch with the UNITA leader almost every day. She said “Gato” ate heartily, like a man who had been literally starving for several weeks. In fact, shortly after his arrival in Luanda, “Gato” was reportedly hospitalized with severe abdominal pains. Like the starving victims of the concentration camps in Europe after World War II, he had almost gorged himself to death.

When I saw “Gato” in Washington a few months later, when he arrived to testify before a House subcommittee, he was still painfully thin. Lucky to be alive, “Gato” remained loyal to Savimbi, invoking his dead leader’s name and example.

No longer concerned about military matters or his daily survival, “Gato” and his old comrade, Manuvakola, began to fight over the leadership of UNITA’s political wing in preparation for national elections, now set for 2006. However, both men were defeated in June 2003 by former UNITA diplomat Isaias Henrique Ngolo Samakuva, who was elected at a party congress outside Luanda as UNITA’s new leader. The government actually wanted a credible opposition party to consolidate its political legitimacy. UNITA appeared to be the only political group with a chance of filling the bill as the MPLA’s designated opponent in future general elections.

Almost forgotten in the whirlwind of political change and peace was the man whose death had made all of this possible. Few people even mentioned the name of the late Jonas Malheiro Savimbi. Posterity is unlikely to give the world a flattering image of the life-long guerrilla, who died as he lived – fighting in the bush, far from Luanda, and light years away from his goal of ruling Angola.

During the almost 10 years he lived after Angola’s ill-fated elections, Savimbi and the MPLA had collectively laid waste to the country. They had put the vast resources of the country at their personal disposal, leaving the people of one of Africa’s potentially-richest countries largely destitute. Both sides had essentially held their countrymen hostage as they engaged in one of the most destructive zero-sum contests the continent has ever seen.

Most of Angola’s cities were in ruin. Its infrastructure of roads, bridges, factories and railroads were devastated or in utter disrepair. The countryside was heavily-mined and scarred, ensuring that unexploded ordinance would continue to claim the lives of innocent Angolans long after the shooting between the government and the rebels ended. The country ranks only behind Egypt and Afghanistan as the country with the highest number of land mines, but leads the world with the highest number of per capita amputees.

Hundreds of thousands of Angolans had fled to neighboring countries, where they lived the desperate existence of refugees. About a third of its population of 10 million people were displaced, with little hope of returning to their home villages to resume normal lives.

The unenviable task of economic reconstruction, even in a country blessed with such enormous natural resources, was almost beyond comprehension. It would take many years to even return the devastated country to the perilous condition it was in when before the civil war resumed. But without the convenient excuse of fighting a war, the victorious MPLA government would come under greater domestic pressure to finally make good on its almost forgotten promises of improving the lives of all Angolans.

Peace had finally come to Angola. And, perhaps, there was a real opportunity to make a start in Angola for the first time in decades.

The mathematical equation by which this new situation had been arrived at was simple: addition by subtraction. Savimbi had proven he could agree to peace, but also that he was constitutionally incapable of abiding by any agreement that did not give him total power. But most Angolans appeared more intent on focusing on a future of possibilities, instead of dwelling on the mechanics of the transition from war to peace.

After Savimbi was killed, the government initially announced that his body would be brought back to the capital for a public viewing. Concerns over protecting the body reportedly prompted those plans to be scrapped. Appeals were made by some of Savimbi’s numerous wives and children to have the body handed over to them for burial at his birthplace in Bie. Yet, the possibility of permitting Savimbi’s grave to be transformed into a shrine, or even allowing the rebel leader to achieve the lofty status of a martyr, was inconceivable.

Ultimately, the government decided to bury Savimbi’s body in pauper’s grave in a small cemetery in Luena, in the same Moxico province where he died. Although the UNITA founder was buried, he did not rest in peace.

At last mention, the government had to post guards at Savimbi’s gravesite 24-hours-a-day, seven days a week, not to restrict access to the former guerrilla’s supporters, but to prevent irate Angolans from desecrating the body — for good reason. A year after Savimbi’s death, members of the UNITA leader’s family asked the government to exhume the body so that it could be reburied in Lopitango, near his birthplace of Andulo. That request was denied. Even now, many of Savimbi’s family members, including several wives and as many as two dozen children, say they have never been to the grave and don’t even know where the former rebel leader’s body has been interred.

Then nearly six years after Savimbi’s death, his modest tomb was vandalized in January 2008, reportedly by four MPLA activists. A plaque memorializing Mais Velho was stolen. Two of the activists were later arrested and UNITA called for an investigation. It seemed that even if Savimbi wanted to rest in peace, there was still too much hatred among his enemies to allow this. But time has marched on.

Savimbi’s name is rarely mentioned at all in Angola nowadays or anywhere else. His photos were conspicuous by their absence at UNITA’s June 2003 party congress outside Luanda. And when the rebel leader’s name does surface, it’s usually used in one of those frequent Internet scams, when one of the former UNITA leader’s alleged children makes an impassioned appeal to some prospective foreign dupe for help in gaining access to one of Savimbi’s multi-million dollar Swiss bank accounts.

Savimbi, or at least a cyber version, has emerged as a video game character in the popular “Call To Duty: Black Ops 2.” The video Savimbi bears a close resemblance to the real article.

But perhaps Savimbi’s most enduring legacy will be the bitterness and vengeance that he engendered from his countrymen.

In Lisbon, some diehard UNITA supporters organized a public memorial for Savimbi shortly after his death was confirmed. Some mourners lit candles beneath photos of the rebel leader.

Three weeks after his death, dozens of “Mais Velho’s” old friends, from the Cold War days in Washington, including former Reagan’s former U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick, gathered one evening for a testimonial dinner for Savimbi at the distinguished, Army and Navy Club on Capital Hill. Those attending stood up amid the heavy wood-paneled walls from their overstuffed leather chairs and couches and raised their glasses in honor of the late UNITA leader.

Savimbi was “extraordinarily educated, intelligent and cosmopolitan – a guerrilla leader on our side,” said Kirkpatrick, recalling the high regard in which the rebel leader was held during the Reagan era. “He was a courageous, dogged and determined leader of the people who followed him.”

David Keene of the American Conservative Union described Savimbi’s death as “a great loss.”

Bradford Phillips, the president of the Persecution Project Foundation (PPF) waxed eloquent when he spoke of Savimbi, who he said had represented hope for those people who were being persecuted in Angola.

“He was a heroic Christian leader who relied on his faith for strength, courage and wisdom to wage a lifelong struggle for the freedom of the Angolan people,” said Phillips. “He was one of the most promising leaders of our times.”

But, perhaps, many of the sentiments expressed overseas for the late UNITA leader were misplaced. His Americans admirers seemed unconcerned with anything other than Savimbi’s “anti-Communist” and religious credentials, not that they had been shamelessly manipulated by a man that more than one former Bush administration official had belated described as a psychopath. That he was ultimately done in with the assistance of the Israelis – who privately bragged about it – the “chosen ones” to most of Washington’s neo-con faithful, adds a delicious sense of irony.

None of Savimbi’s U.S. admirers had lived in Angola, although a few had visited Jamba several years before. They never had to face the wide-scale destruction Savimbi had wrought in the single-minded in pursuit of his political ambition, which had cost millions of his own people so dearly. In the end few Angolans lamented his passing. It seems to matter little to nearly anyone in Angola how Savimbi had met his end, only that he was finally gone.

Phone call gave Savimbi away

News 24

26 February 2002

Lisbon – Angolan army officers were able to locate and kill veteran rebel leader Jonas Savimbi by tracking a telephone call he made to Lisbon from his forest hideout, daily Diario de Noticias said on Tuesday.

The paper, which did not identify a source for its information, said the call was made on February 13 from eastern Moxico province, eight days before Savimbi was killed in a clash with government troops in the same region.

A member of a Unita military unit protecting Savimbi also made a call to Paris the day before Savimbi was killed, Diario de Noticias added.

The call was made from roughly 70km from the area where Savimbi was killed, it said.

The charismatic 67-year-old Savimbi, who had led Unita rebels in a brutal civil war that has raged almost non-stop since independence from Portugal in 1975, was buried on Saturday.

Portugal on Monday denied any involvement in the Angolan army operation in which the veteran rebel leader was killed.

A representative of Savimbi’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (Unita) told Lisbon private radio TSF on Monday that Israeli, Portuguese and South African troops helped Angolan forces find the rebel leader.

‘We nailed Savimbi seven times’

IOL

Feb 25, 2002

Luanda – Angolan rebel leader Jonas Savimbi fought until the very end, army officials have said, detailing their final battle with the man who led his forces through almost 27 years of civil war.

Savimbi was killed on Friday together with 21 of his bodyguards, all with weapons in hand, on the banks of the Luvuei River in the eastern province of Moxico, Brigadier General Simao Carlitos Wala told the official Jornal de Angola.

“Savimbi decided to rest. Confident, as always, he had nonethless placed his units on alert.

“Too late – we already had surprised them. He fought back with gunfire, and that’s why he was killed,” said Wala, who led the army in the battle that killed Savimbi.

“We nailed him seven times. He tried to resist with his gun, but then he was dead,” Wala told state radio.

Savimbi was shot 15 times – in the throat, head, torso, legs and arms, state media said.

Wala said Savimbi’s battle plan had failed because he had lost radio communication, following an army offensive dubbed Kissonde, named after an aggressive ant.

“He only had a small ground to air radio.

“This factor blocked any chance Savimbi had to get some security from parallel units, which would have allowed him to cross a stretch of the river up at the border,” Wala said.

He did not say whether Savimbi had planned to cross into Zambia, but the Jornal de Angola cited army officials as saying he had planned to go to the Zambian border, where a unit of his rebels “were waiting to guide and defend him”.

Wala’s lengthy interviews with state media provided the most detailed account yet on the circumstances surrounding the fate of the veteran rebel leader, who died after spending most of the last 40 years in armed conflict in the country.

The Jornal de Angola, the only newspaper printed in the nation, ran a 10-page special issue on Sunday on Savimbi’s death.

Army soldiers had waged a tough battle to penetrate deeply enough into the rebel forces’ stronghold to reach Savimbi and the guards who surrounded him, Wala said.

Savimbi had used his gun in a vain attempt to stave off the army attack, only 80km from the Zambian border, Wala said.

“Savimbi knew the area very well. He was like a fish in water,” Wala said.

The army had managed to target Savimbi because two of his most important military leaders, known as Brigadier Mbule and Big Joy, had already been killed, Wala said.

The two men had led the elite units of Savimbi’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (Unita), which were responsible for creating diversions aimed at disrupting army operations, Wala said.

One of Savimbi’s wives, Catarina Savimbi, had been seriously injured in the attack and taken to a clinic in Luena, Moxico’s capital, for treatment, the newspaper said.

Savimbi was buried on Saturday in Lucusse, under a tree near where he was killed, the Jornal de Angola said.

Jonas Savimbi: “Washington’s Freedom Fighter,” “Africa’s “Terrorist”

Institute for Police Studies

February 1, 2002

Peace is back on the agenda, if not yet on the horizon in Angola. With the death of rebel leader Jonas Savimbi and the state visit to Washington by Angolan president Jose Eduardo dos Santos, there is again a glimmer of hope that the country’s 27-year-long civil war may finally be coming to a real end. As Salih Booker, Director of Africa Action, puts it, “Savimbi’s death removes the principal obstacle to peace in that country. So long as he was alive, it seemed virtually impossible that Angolans would ever be able to conclude and implement a peace settlement. But his death does not automatically ensure that peace will follow.”

Following the February 22nd ambush and murder of the 67-year-old veteran rebel leader by the Angolan army, obituaries in the American press have described his remarkable charisma and ferocious drive for power. He is, indeed, an African paradox, who as leader of sub-Saharan Africa’s longest running civil war, continues to perplex and shame many of his own co-conspirators. Savimbi is widely seen as responsible for a nearly nonstop war that has taken nearly one million lives and as the principal spoiler of the Angolan elections and United Nations-backed peace plans in the early 1990s. As the Namibian government said in announcing his death, “Savimbi chose the way of terrorism and turned Angola into a land of many killing fields.” When news of Savimbi’s death reached the Angolan capital of Luanda, people took to the streets chanting, “The terrorist is gone.”

The United States bears some blame for Angola’s brutal civil war because Savimbi was long the darling of American right-wing, conservative politicians and the CIA. Some fifteen years ago, President Ronald Reagan invited Savimbi to the White House and hailed him a “freedom fighter” for his efforts to oust dos Santos and the leftist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA)–the party that has ruled Angola since its independence in 1975.

President George W. Bush’s meeting with dos Santos, just four days after Savimbi’s death is both illustrative of the Washington’s erratic involvement in Angola and a signal that these days Washington is more interested in Angola’s resources–oil and diamonds–than its ideology. But, if war is to end in this troubled country, the international community must work quickly and persistently to broker a peace deal and disarm the rebel combatants.

Savimbi first took to the bush in the early 1960s as Angolans began organizing against 400 years of Portuguese colonial rule. Billed as an anticommunist during the height of the cold war, Savimbi was actually no more than a power-hungry opportunist who changed his colors to suit the tastes of his particular financial backers. His enigmatic character confounded a great number of powerful people over the years. In 1999, for instance, one former U.S. diplomat told me in an informal conversation just how unsettling Savimbi’s personality could be. This official, who had met the rebel leader over 25 times while he was in hiding, conceded each time he felt that he was in the presence of “pure evil.” He explained that Savimbi was “so charming, intelligent, articulate, and dangerous” that he frequently had to spend return flights to Luanda “deprogramming African-American delegations who were charmed into thinking that Savimbi’s vision for Angola was the right one.”

Jonas Savimbi, a member of Angola’s largest ethnic group, the Ovimbundu, was born and raised in the southern Angolan province of Moxico. A bright, charismatic, former doctorate student, Savimbi became fluent in more than six languages–including Portuguese, French, and English. His knack for learning languages boosted his credibility among the various groups with whom he negotiated. His gift in European languages facilitated his dealings with political opponents, diplomats, and foreign reporters, while he switched into Umbundo when rallying his followers among the Angolan people.

At the start of the Angolan independence struggle in 1961, Savimbi originally tried to acquire a leadership post within the MPLA, the principal national liberation group. However, the MPLA, which was backed by the Soviet Union, only offered him a rank-and-file militant position. Feeling rebuffed, Savimbi aligned with rebel commander Holden Roberto’s anti-colonial group, the Union of Peoples of Angola (UPA), as it offered him a more prestigious rank as minister in its government in exile.

By 1964, Savimbi decided to resign from the UPA, claiming that Roberto (who was related to and backed by Zaire’s pro-American dictator Mobutu Sese Seko) was a stooge for the “American imperialists.” In 1966, Savimbi launched a third movement, the United Front for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Savimbi and other top UNITA leaders had received guerrilla warfare training in China from 1965 to 1966. And, over the next decade, China supplied the rebel movement with weapons and war material.

Since the start of the Angolan liberation struggle, Savimbi had touted himself as a nationalist fighting for independence from Portuguese colonialism. However, Savimbi showed more hostility toward the other indigenous freedom parties and forged a clandestine alliance with the Portuguese colonial government and its secret police, PIDE, according to University of Southern California professor Gerald Bender and a series of subsequently released documents. As part of this alliance, code-named “Operation Timber,” Savimbi and PIDE engaged in military actions against rival movements, and Savimbi provided the Portuguese with information regarding the activities of the opposition forces. After the Portuguese withdrew from Angola in 1974, Savimbi thwarted an agreement for multiparty, nationwide elections in November 1975, returned to the bush, and plunged the nation into another two decades-plus of war.

During the liberation struggle when Savimbi was receiving most of his aid from China, he boasted to reporters of his Maoist ideology. However, following independence, Savimbi strove to cut a better deal in the West. Declaring himself a capitalist, the charismatic rebel leader had, within a short time, joined Holden Roberto on the CIA’s payroll in a civil war against the Soviet-backed MPLA.

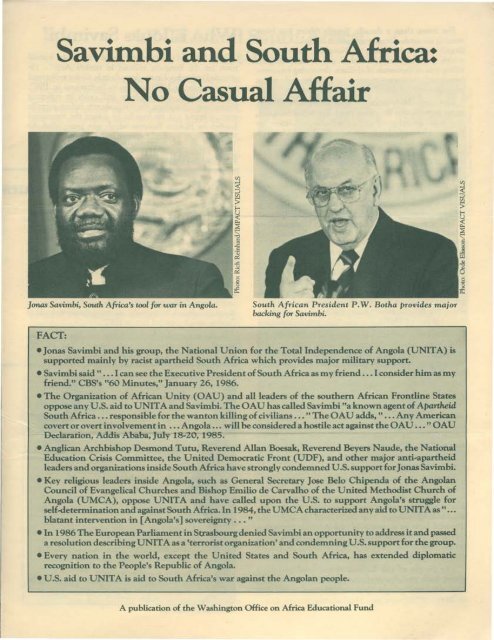

Roberto soon fell by the wayside, but Savimbi, as Washington’s favorite, received in the early 1980s over $15 million in covert military aid from the Reagan administration, and, in the late 1980s, another $15 million from the Bush Sr. administration. This thrust the U.S. into an unsavory alignment with white-ruled South Africa, which not only supplied UNITA with money, arms, and material, but also frequently deployed troops into Angola and launched air strikes on MPLA positions. The U.S. was repeatedly warned against aligning with South Africa and backing UNITA. In a January 1986 statement, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) said, “Mr. Savimbi is a known agent of apartheid South Africa, and has been responsible for the wanton killing of civilians, the destruction of economic infrastructure of the country, and the destabilization of the legitimate Government of the People’s Republic of Angola. Any American involvement in the internal affairs of Angola … will be considered a hostile act against the OAU.”

Even U.S. officials warned against such unsavory alliances. Wayne Smith, a former career Foreign Service officer, cautioned that entering into a joint U.S.-South African pact would “undermine U.S. relations with black Africa for years to come.” Richard Moose, former Assistant Secretary of State, also advised against the U.S. joining with South Africa in its battles against the Angolan government. In testimony in 1986 before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Moose cautioned that to join or replace the South Africans as Savimbi’s primary supporter “would be more than the Russians could hope for.” Moose speculated, “In fact, I sometimes wonder whether Savimbi, educated in Marxism and trained by the Maoists, is not still the Communists’ secret weapon in southern Africa.”

Whatever the case, Savimbi certainly showed his skill as a political chameleon. In 1988, several former UNITA members reported to the Portuguese newsweekly, Espresso, that UNITA’s political elite all followed the precepts of Savimbi’s Practical Guide for the Cadre, which was described as “a manual of dialectical materialism and Marxism-Leninism with a distinct trait of Stalinism and Maoism.” The UNITA dissidents claimed that the Guide was taught in a room filled with Lenin and Mao Tse-Tung busts, where the anthem of the Communist International was sung every day. These former UNITA members denounced as fraudulent Savimbi’s widely publicized pro-Western ideology and defense of democracy. They pointed out that there was a huge discrepancy between what UNITA claimed abroad as its objectives (i.e., negotiations with the MPLA, reconciliation, and coalition) and what the Guide taught. The Guide, said to be written by Savimbi, was considered a secret book accessible only to the political elite of UNITA.

For decades, Savimbi’s forces fought Angola’s MPLA government, which was supported militarily by the Soviet Union and thousands of Cuban troops–and was recognized by every country in the world except South Africa and the United States. In order to instill terror in the population and to undermine confidence in the government, Savimbi ordered that food supplies be targeted, millions of land mines be laid in peasants’ fields, and transport lines be cut. As part of this destabilization effort, UNITA frequently attacked health clinics and schools, specifically terrorizing and killing medical workers and teachers. The UN estimated that Angola lost $30 billion in the war from 1980 to 1988, which was six times the country’s 1988 GDP. According to UNICEF, approximately 330,000 children died as direct and indirect results of the fighting during that period alone. Human Rights Watch reports that because of UNITA’s indiscriminate use of landmines, there were over 15,000 amputees in Angola in 1988, ranking it alongside Afghanistan and Cambodia.